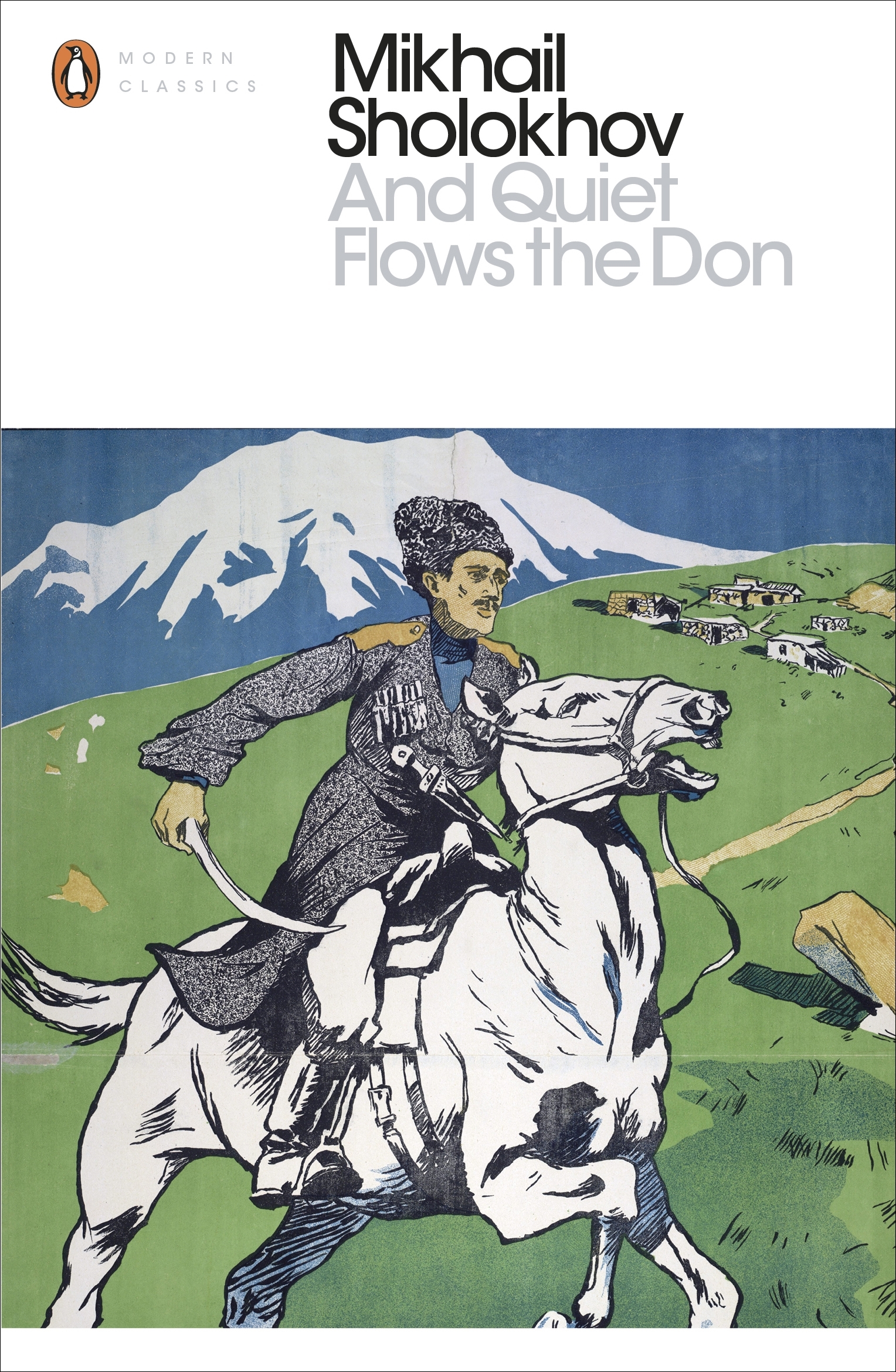

In the flow of twentieth-century world literature, there are works that do not exist merely as stories retold, but as spiritual testimonies of an entire era – where history does not appear as rigid timelines or dry events, but seeps deeply into individual destinies, personal choices, and everyday tragedies. And Quiet Flows the Don is such a work.

More than an epic of the Don River region and the Cossack people, the novel is a vast panoramic portrayal of Russia during its most violent and transformative years: from the First World War, through the October Revolution, to the Russian Civil War – upheavals that shook the foundations of society, morality, and human belief.

The title And Quiet Flows the Don evokes calmness and tranquility, yet it is in fact a deeply paradoxical metaphor. The river flows silently on, while along its banks lie lives torn apart by violence, hatred, and irreversible choices. This very contrast creates the novel’s haunting power, allowing it to transcend the boundaries of historical fiction and become a classic of universal significance – one that views human beings not as instruments of history, but as both its victims and its witnesses.

1. The Author and the Work

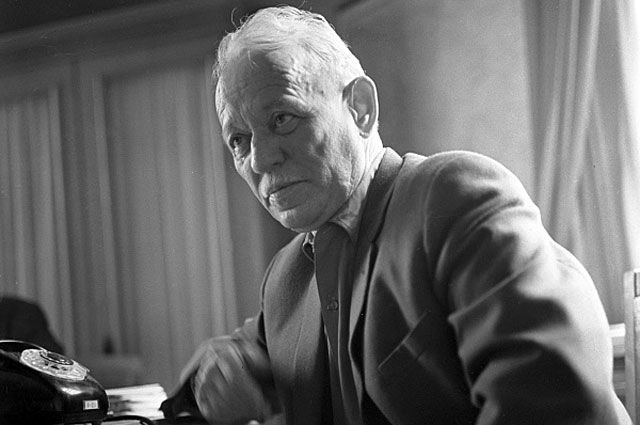

Mikhail Sholokhov (1905–1984) is one of the most prominent figures in twentieth-century Russian – Soviet literature. He was born and raised in the Don steppe, among the Cossack community – a people with a distinct history, culture, and identity, deeply rooted in military tradition, a strong sense of freedom, and communal pride. This environment became the enduring source of inspiration throughout Sholokhov’s literary career.

What gives Sholokhov’s writing its unique value is that he did not write from the detached perspective of an outside observer, but from lived experience. He witnessed war, revolution, the collapse of old values, and the painful formation of a new social order. As a result, his works are intensely realistic – harsh yet not cold, tragic yet not hopeless.

And Quiet Flows the Don was written over more than a decade (1928–1940) and consists of four volumes, remarkable for both its length and artistic ambition. In 1965, the novel earned Sholokhov the Nobel Prize in Literature, with the citation highlighting the artistic power and integrity with which he depicted a decisive period in Russian history.

Unlike many ideologically driven novels of its time, And Quiet Flows the Don does not impose a single doctrine. Sholokhov places human beings – with all their contradictions, mistakes, weaknesses, and desires – at the center of history. This choice allows the novel to achieve both epic scope and rare human depth.

2. Summary of the Plot

The setting of And Quiet Flows the Don stretches across the Don steppe, home to generations of Cossacks living within a tightly bound system of values. Here, individuals are defined not only by personal character, but by family lineage, military tradition, communal honor, and collective duty. This cultural environment forms the foundation for all the conflicts in the novel.

At the center of the story is Grigory Melekhov, a Cossack man driven by powerful instincts, fierce individuality, and deep inner conflict. From the opening pages, Grigory appears as a divided soul – torn between desire and responsibility, between the call of the heart and the moral framework imposed by his community. His life is shaped not by a single turning point, but by a series of painful choices, each leading to loss.

The love affair between Grigory and Aksinya forms the novel’s first major emotional axis. Aksinya is not merely a lover; she symbolizes the longing for freedom, instinctive life, and escape from oppression. Forced into marriage with a violent husband, she finds in Grigory both physical and emotional liberation. Their love is intense, passionate, and rebellious – and precisely for that reason, incompatible with Cossack moral order. Society refuses to forgive them, and tragedy begins the moment they dare to live truthfully with their emotions.

In stark contrast to Aksinya stands Natalya, Grigory’s lawful wife. Natalya represents the traditional Cossack woman: gentle, patient, devoted, and self-sacrificing. Her tragedy does not erupt violently, but unfolds slowly and silently. She loves Grigory with total devotion, yet lives in constant abandonment. Through Natalya, Sholokhov exposes the quiet suffering of women in a patriarchal society, where endurance brings no redemption – only prolonged pain.

With the outbreak of the First World War, Grigory and many young Cossacks are swept into battle. War is portrayed not as heroic adventure, but as a machine that crushes human beings. On the front lines, Grigory shows bravery and combat instinct, yet soon recognizes the emptiness of killing. Medals bring no lasting pride, only inner void and doubt. His faith in traditional values begins to fracture.

The October Revolution and the Russian Civil War push the Cossack community into even deeper tragedy. People who once lived in relative stability are forced to choose sides: the Red Army, the White forces, or local factions. Grigory repeatedly changes allegiance – not out of opportunism or betrayal, but from his inability to find an absolute truth. He realizes that every side claims ideals, yet all are willing to trample individual lives.

Grigory’s personal tragedy runs parallel to the historical catastrophe. Aksinya is killed while fleeing with him – her death marks not only the loss of love, but the total collapse of the dream of living outside history. Natalya also dies after enduring irreparable emotional wounds, leaving Grigory burdened with guilt and emptiness. His family is destroyed, his homeland ravaged, and the Cossack community gradually loses its identity.

In the final chapter, Grigory returns to the village of Tatarsk, exhausted in both body and spirit. He no longer believes in any political ideal, nor does he possess the strength to rebel. The only thing anchoring him to life is his young child – a symbol of continuation, of life persisting beyond devastation. The image of Grigory holding his child by the Don River closes the novel on a profound, subdued note: history may sweep away all values, but the human instinct to love, protect, and endure flows quietly on – like the Don itself.

3. Ideological and Artistic Value

A Humanistic View of History and Human Tragedy

The core ideological value of And Quiet Flows the Don lies in Sholokhov’s portrayal of history not as an abstract ideological process, but as a ruthless force acting directly upon real human lives. War, revolution, and civil conflict are not idealized as necessary steps toward a “brighter future,” but shown in all their chaos, contradiction, and brutality.

Sholokhov focuses especially on those at the bottom of history – peasants, soldiers, ordinary Cossack families – who do not make history but pay the highest price for it. He reveals that history does not merely alter borders or governments; it shatters the most fundamental human bonds: family, love, faith, and cultural identity.

The novel’s central question is not “which side is right,” but a deeper existential one:

How much humanity can a person preserve when placed in inhuman conditions?

Grigory Melekhov embodies this dilemma. He cannot stand outside history, yet lacks the faith to fully merge with any ideology. His hesitation, confusion, and failure are not signs of weakness, but the tragedy of a man honest with his conscience. Through Grigory, Sholokhov portrays the tragedy of an entire generation – forced to choose when every choice leads to loss.

The novel’s profound humanism is further expressed in its depiction of love, family, and life standing in direct opposition to historical violence. The deaths of Aksinya and Natalya are not merely personal tragedies, but silent indictments of an era in which private happiness had no place before the machinery of war and revolution.

The Tragedy of Cossack Cultural Identity

Another significant layer of meaning in And Quiet Flows the Don is the disintegration of traditional Cossack identity. Under historical pressure, a community once grounded in honor, military tradition, and autonomy becomes divided, fractured, and directionless.

Sholokhov does not idealize the Cossacks as flawless heroes, yet he portrays them with deep empathy. The collapse of Cossack order results not only from political upheaval, but from internal erosion, as old values fail to sustain people amid new realities.

The novel poses a universal question:

When a community loses its foundational values, what can individuals cling to in order to survive?

Sholokhov’s answer lies not in ideology, but in the most instinctive bonds – parenthood, human connection, and the will to live – clearly embodied in the novel’s ending.

A Large-Scale Realist Epic Structure

Artistically, And Quiet Flows the Don reaches a rare level of realist epic achievement in twentieth-century literature. Sholokhov constructs a vast fictional space spanning many years, encompassing both private lives and national upheavals.

Despite its monumental scale, the novel avoids rigidity or diffusion. Its structure interweaves personal destinies with historical events, ensuring that every political upheaval is reflected through concrete human experience. History is not a backdrop, but a direct force shaping the psychology, actions, and choices of the characters.

4. Memorable Quotations

One of the enduring strengths of And Quiet Flows the Don lies in its lines rich with philosophical weight, where language not only tells a story but carries pain, confusion, and existential tragedy. Sholokhov’s prose is restrained and calm, yet beneath it runs an intense emotional current and deep reflection on human fate under historical storms.

Rather than overt condemnation or didactic philosophy, Sholokhov allows images, emotions, and lived experience to speak for themselves. Below are several representative passages that capture the novel’s tragic, humanistic, and haunting spirit:

- “The Don kept flowing, indifferent to human pain and spilled blood.”

- “War wore people down to the core, leaving empty souls among the living.”

- “Grigory felt like a man lost, unable to find either a shore or a way back.”

- “Love, placed between hatred and violence, becomes both salvation and destruction.”

- “No truth is great enough to soothe a mother’s grief for her dead child.”

- “Human beings are born to live, yet history teaches them how to kill.”

- “In war, one may win a battle, but always loses something within.”

- “Honor and ideals grow fragile when paid for with the blood of loved ones.”

- “Grigory understood that whichever side he chose, he was fighting himself.”

- “Nature still bloomed, seasons still came – only human beings were no longer whole.”

- “No one leaves war as the same person they once were.”

These lines do more than depict war and revolution as historical events; they reveal the lasting spiritual damage inflicted by violence. They leave behind a lingering resonance, compelling readers to reflect on the unspoken question the novel poses: how much sacrifice does history have the right to demand from human beings?

5. Conclusion

And Quiet Flows the Don is not an easy novel to read, but the slower and more carefully it is read, the more its intellectual depth and enduring human value emerge. It offers no immediate comfort, but leaves behind a lasting echo – a quiet sorrow for human fate in the face of history.

The novel’s greatest strength lies in its brutal honesty tempered by compassion. Sholokhov does not console readers with happy endings; instead, he confronts us with a harsh truth: history is written in blood, tears, and broken dreams. Yet within this devastation, the final image of a father holding his child kindles a fragile but persistent light – a belief in humanity’s capacity for renewal.

That is why, after many decades, And Quiet Flows the Don retains its full weight and relevance – like the Don River itself, flowing silently through time, carrying within it both the beauty and the tragedy of human existence.