There are books that, once closed, seem to continue resonating in the reader’s mind – not through dramatic plot twists, but through unanswered questions that linger quietly. The Da Vinci Code is such a book. It does not merely tell a thrilling detective story; it opens up a journey that challenges history, belief, and the “truths” humanity has long accepted without question.

From the very first pages, readers are drawn into a world where art, religion, science, and power are tightly interwoven. The cold corridors of the Louvre, ancient cathedrals, and seemingly familiar symbols suddenly become laden with hidden meaning. In this world, every painting, every architectural detail, every number can be a clue – or a challenge to how we understand history itself.

What makes The Da Vinci Code distinctive is not whether it is academically right or wrong, but the fact that it dares to ask questions. Dan Brown does not demand that readers believe his story; instead, he invites them to doubt, to think, and to search for their own answers. This intellectual provocation is precisely what transformed the novel into a global phenomenon, far exceeding the boundaries of conventional entertainment.

To read The Da Vinci Code is to enter a quest aimed not only at uncovering a hidden secret, but also at examining one’s own inner convictions: what do we believe, why do we believe it, and can those beliefs withstand the darker corners of history? More than two decades after its publication, the novel continues to be reread, debated, and analyzed – a reminder that literature, when it touches the pulse of its era, can exert a lasting and profound influence.

1. Introduction to the Author

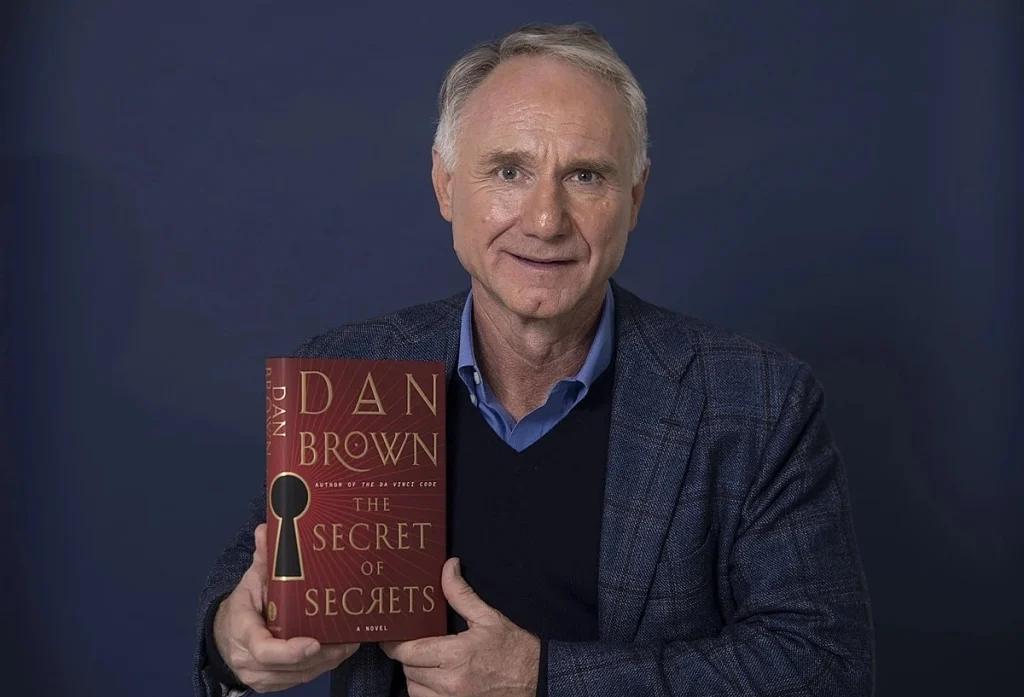

Behind the global phenomenon known as The Da Vinci Code stands Dan Brown, a writer who did not follow a traditional academic path, yet possesses a rare ability: transforming dense knowledge of history, symbolism, and religion into a compelling narrative accessible to millions of readers worldwide.

Dan Brown was born in 1964 in the United States, into a family with a strong intellectual foundation. His father was a mathematics professor, while his mother was a church musician. This environment shaped two parallel modes of thinking from an early age: the logical, rational mindset of science and the spiritual depth of religion. Their intersection later became the core material of many of his novels, most notably The Da Vinci Code.

Unlike authors who pursue purely literary expression, Dan Brown approaches fiction as an act of deciphering. He is fascinated by codes, symbols, secret societies, and the gaps within official history – spaces where truth, power, and belief collide. The character Robert Langdon, who appears throughout his works, can be seen as Brown’s intellectual alter ego: a scholar who rejects fanaticism, embraces skepticism, and seeks to reinterpret the world through signs and symbols.

What makes Dan Brown a controversial figure is not his writing style, but his intellectual ambition. He does not shy away from touching the most sensitive areas of Western religion and history – domains guarded by centuries of tradition and authority. Yet Brown has never claimed to be a historian or theologian. He is a storyteller, using history as a backdrop to raise questions rather than to deliver final answers.

For this reason, Dan Brown’s works – especially The Da Vinci Code – have consistently provoked divided responses: one side hails him as a master of popular fiction, while the other criticizes his academic simplifications. Still, it is undeniable that he achieved something rare: bringing seemingly distant subjects such as Christian symbolism, secret societies, and suppressed history into mainstream cultural discussion.

In this sense, Dan Brown is more than the author of a bestselling novel. He is a figure who reshaped how general readers engage with knowledge – through curiosity, storytelling, and an unrelenting spirit of inquiry.

2. Summary of the Plot

The Da Vinci Code opens in an atmosphere of tension and mystery at the Louvre Museum, a space traditionally devoted to art and beauty. Jacques Saunière, the museum’s chief curator, is murdered in the final moments of his life. Yet his death is far from ordinary. Before dying, Saunière arranges his body in a symbolic pose and leaves behind a series of cryptic symbols and codes – a message intended to transcend death itself.

Robert Langdon, an American professor of symbology visiting Paris, is suddenly drawn into the investigation as a suspect. Very quickly, however, Langdon realizes that the symbols Saunière left behind were not acts of desperation, but a carefully constructed system of codes meant for someone fluent in the language of art and symbolism. Assisting him is Sophie Neveu, a young cryptographer and Saunière’s granddaughter. What begins as an uneasy collaboration gradually deepens as layers of hidden truth are uncovered.

The investigation soon turns into a breathless flight. Langdon and Sophie are pursued not only by French authorities, but also by shadowy forces operating within the Church. Each clue leads them from Leonardo da Vinci’s artworks to ancient codes concealed in architecture and religious rituals. Every solution opens yet another door – deeper, darker, and more dangerous.

At the heart of the mystery lies the Holy Grail, one of Christianity’s most sacred symbols. Yet Dan Brown radically reinterprets its meaning. In this narrative, the Grail is not a physical relic, but a living secret: the bloodline of Mary Magdalene and Jesus Christ, protected for centuries by an ancient secret society known as the Priory of Sion. According to this version of history, official narratives were deliberately rewritten, while the role of women in Christian civilization was systematically erased.

Running parallel to this intellectual pursuit is the dark storyline of Silas, a fanatical monk affiliated with Opus Dei. Silas embodies the destructive side of faith taken to extremes, where blind obedience justifies violence. He is not merely a pursuer, but a tragic reflection of what happens when belief is stripped of compassion and self-reflection.

The novel’s climax is not defined by a dramatic confrontation, but by revelation. Figures who appear to guide the protagonists are exposed as manipulators behind the entire scheme. Sophie Neveu, once a bystander, becomes central to the hidden history when she discovers her true identity as part of the preserved bloodline.

The ending of The Da Vinci Code does not culminate in a public disclosure, but in a profoundly human choice: the secret is preserved, the truth passed on quietly. Dan Brown closes the story not with an explosion, but with silence – leaving readers to wonder whether the world is ready to face the whole truth, or whether belief sometimes needs protection for society to endure.

3. Thematic and Artistic Value

The enduring value of The Da Vinci Code does not lie in how historically accurate it is, but in how it forces readers to reconsider the ways history and belief are received. Dan Brown does not write to deliver ultimate truths; he writes to disrupt the comfort of “accepted truths,” creating space for dialogue between faith, reason, and power.

At its deepest level, the novel is a story about control over knowledge. History, as portrayed here, is not an objective flow of events, but the result of deliberate choices – what is preserved, what is erased, and who has the authority to decide. Through the Grail hypothesis and the hidden bloodline, Brown poses a disturbing yet necessary question: does official history truly reflect the whole truth, or merely the version that best serves existing power structures?

One of the novel’s most controversial yet intellectually rich aspects is its treatment of religion. Brown neither rejects faith nor promotes atheism. Instead, The Da Vinci Code criticizes extremism and dogma when religion becomes institutionalized and weaponized. Silas stands as a stark illustration of the tragedy that occurs when faith loses empathy and turns into blind submission. The underlying message is clear: the problem lies not in belief itself, but in how belief is used.

The novel also carries significant humanistic value by reasserting the role of women in Western spiritual history. The portrayal of Mary Magdalene – though controversial – serves as a symbol of voices silenced by authority. Brown does not merely invent fiction; he reflects a historical reality in which women’s roles were repeatedly erased from dominant narratives. This element allows The Da Vinci Code to transcend the detective genre and engage with broader social questions.

Artistically, Dan Brown demonstrates exceptional control over narrative structure. The novel unfolds like a chain of interlocking codes: each solution leads not to closure, but to another mystery. Short chapters, rapid pacing, and frequent cliffhangers create relentless momentum. While these techniques are common in popular fiction, Brown elevates them by integrating historical knowledge and symbolic interpretation.

The language of The Da Vinci Code is not ornate in a classical literary sense, but it is highly effective. Brown favors clarity and direct exposition, making complex ideas about art, architecture, and religion accessible to general readers. Although this accessibility has drawn criticism from literary purists, it is precisely what allowed the novel to achieve global reach.

Most importantly, The Da Vinci Code succeeds in turning readers into participants. They do not merely follow Robert Langdon’s journey; they instinctively begin decoding, doubting, and questioning alongside him. When the book ends, what remains is not full satisfaction, but an intellectual void – a space in which readers continue reflecting on the boundaries between truth and belief, knowledge and authority.

It is here that The Da Vinci Code proves its lasting significance. It may be disputed and criticized, but it cannot be ignored. In popular literature, a work that provokes debate, inquiry, and deep reflection is, in itself, a remarkable achievement.

4. Memorable Quotations

One reason The Da Vinci Code retains its vitality lies not only in its gripping plot, but in its concise yet thought-provoking lines. Dan Brown avoids extended philosophical monologues; instead, he places deceptively simple statements in his characters’ mouths – statements that strike at fundamental questions of history, belief, and power.

The following quotations function as reflective pauses within the narrative, moments that compel readers to slow down and think rather than simply follow the story’s pace.

“History is always written by the winners.”

In Brown’s view, history is not absolute truth, but selective narration. This line serves as a warning: what we learn may only be the victor’s version.

“The Bible did not arrive by fax from heaven.”

Provocative yet grounded, this statement emphasizes that religious texts passed through human hands – and therefore through human influence and power.

“Faith is universal. Our specific methods for understanding it are arbitrary.”

Here, Brown distinguishes between belief itself and the institutions built around it.

“Men go to far greater lengths to avoid what they fear than to obtain what they desire.”

A psychologically acute observation, revealing fear as a stronger motivator than aspiration.

“Nothing is more creative… nor destructive… than a brilliant mind with a purpose.”

This line encapsulates the novel’s central duality: knowledge can enlighten or devastate, depending on intent.

“The greatest cover-up in history is not what people are told, but what they are never allowed to ask.”

Brown focuses not on lies, but on silenced questions – the ultimate form of control.

“Symbols have the power to speak louder than words.”

A declaration of the novel’s aesthetic philosophy: meaning lies beneath the surface.

“Religion is flawed, but only because man is flawed.”

A balanced view that prevents the novel from descending into anti-faith extremism.

“What we believe is often more powerful than what is true.”

Perhaps the clearest expression of the book’s core message: belief shapes reality more forcefully than truth itself.

Together, these quotations form a coherent philosophical thread: truth does not exist independently of belief, and history is never neutral. Brown does not force agreement – he forces reflection.

5. Conclusion

Closing The Da Vinci Code, what lingers is not merely the excitement of a relentless chase, but a series of quiet questions that continue to echo. Dan Brown does not attempt to offer definitive answers about history, religion, or belief. Instead, he challenges readers through doubt and intellectual gaps that demand personal engagement. This deliberate choice allows the novel to transcend the limits of a conventional thriller and become a cultural phenomenon.

From a personal perspective, the power of The Da Vinci Code lies not in its exposure of secrets, but in its willingness to question what is deemed untouchable. The novel reminds us that history is not only what happened, but what was recorded; that belief does not always align with truth; and that controlled knowledge can be as dangerous as any weapon. Brown does not reject faith – he simply insists that humanity should never relinquish the right to think independently.

The Da Vinci Code may not be flawless in literary or academic terms. Yet as a work of popular fiction, it succeeds where few do: it compels millions of readers worldwide to pause, doubt, debate, and reflect. And sometimes, the greatest value of a book is not how correct it is, but how boldly it encourages us to ask more questions – about history, belief, and the way we see the world.