Among the classic novels of Russian and world literature, The Brothers Karamazov – Dostoyevsky occupies a distinctive position due to its ability to combine a complex narrative structure with exceptional intellectual depth. The work does not merely portray the tragedy of a fractured family; it expands into a broad arena of debate on morality, faith, free will, and human responsibility for one’s own actions.

Regarded as Dostoyevsky’s final novel and the pinnacle of his creative achievement, The Brothers Karamazov fully reflects the enduring concerns that run throughout his literary career: the confrontation between reason and faith, instinct and conscience, the desire for freedom and the need for moral order. Through the destinies of the Karamazov family members, the novel places human beings in extreme situations in which every choice inevitably carries ethical consequences.

Far from aiming at mere entertainment, The Brothers Karamazov compels readers to engage in a serious process of reflection. Every conflict and every dialogue functions like a philosophical argument, transforming the novel into a work that is simultaneously literary and intellectual. It is precisely this quality that has allowed The Brothers Karamazov – Dostoyevsky to retain its lasting value and to be continually studied and analyzed across disciplines such as literature, philosophy, and theology.

1. Introduction to the Author and the Work

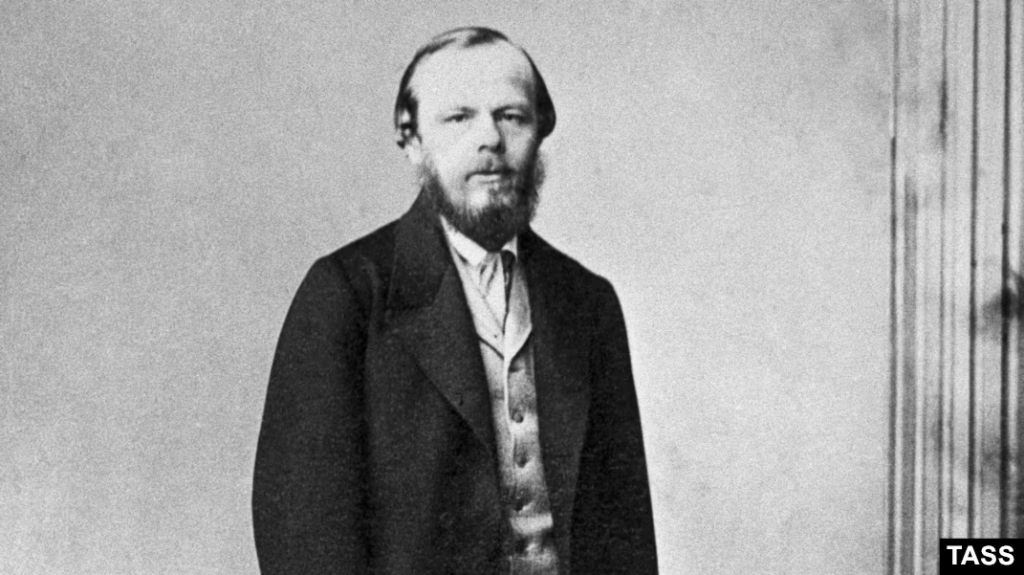

Fyodor Dostoyevsky – A Novelist of Modern Spiritual and Moral Crisis

Fyodor Dostoyevsky (1821–1881) is one of the central figures of nineteenth – century Russian literature and a writer whose influence has profoundly shaped modern literary and philosophical thought worldwide. He is often regarded as a pioneer of the psychological novel and as a writer who laid the groundwork for later intellectual currents such as existentialism, psychoanalysis, and the philosophical novel.

Dostoyevsky’s life was marked by severe upheavals that decisively shaped his artistic worldview. From a death sentence followed by a last-minute reprieve, to years of exile in Siberia, a life of poverty, struggles with epilepsy, and recurring crises of faith, these experiences forged a writer relentlessly haunted by the question: what becomes of the human being when pushed to the ultimate limits of freedom, guilt, and suffering?

Unlike many realist writers of his time who focused on social structures, Dostoyevsky directed his attention to the inner life. His characters do not merely act; they think incessantly, struggle internally, interrogate themselves, and negate their own convictions. In his literary universe, good and evil do not exist as separate entities but intertwine within the same individual, creating moral conflicts that cannot be resolved through simplistic judgments.

The Brothers Karamazov – A Synthesis of Dostoyevsky’s Thought and Art

Published in 1880, The Brothers Karamazov is the final novel of Dostoyevsky’s career and is widely regarded as the most comprehensive synthesis of his philosophical ideas and narrative artistry. The novel emerged during a period of profound upheaval in Russian society, when traditional religious and moral beliefs were increasingly challenged by rationalism and atheistic thought.

In terms of form, The Brothers Karamazov resembles a family novel combined with a crime narrative, centered on the murder of a father. Yet this surface structure merely serves as a vehicle for the exploration of universal intellectual concerns. Through the fates of the Karamazov family members, Dostoyevsky raises fundamental questions: Can human beings live without faith? Does absolute freedom lead to moral chaos? To what extent does individual responsibility exist in a profoundly unjust world?

Each central character in the novel is not only an individual personality but also the embodiment of a particular ideological stance. The Karamazov family thus becomes a microcosm of society itself, where competing value systems confront one another directly: instinct versus reason, faith versus doubt, moral order versus the longing for freedom. This ideological polyphony and the dialogic structure elevate the work beyond the limits of conventional storytelling.

With The Brothers Karamazov, Dostoyevsky does not seek to persuade readers to adopt a fixed worldview. Instead, he constructs a literary space in which all perspectives are articulated to their fullest extent, including those that are extreme or dangerous. As a result, the novel remains an open text, continuously reinterpreted across generations, while retaining its enduring intellectual and scholarly significance.

2. Summary of the Plot

The Brothers Karamazov revolves around the tragedy of the Karamazov family – a family fractured both in blood ties and in moral foundations. The central narrative axis is the murder of the father, Fyodor Pavlovich Karamazov, yet beneath it lies a complex web of intergenerational conflict, opposing value systems, and morally decisive choices.

Fyodor Pavlovich Karamazov – The Father and the Source of Conflict

Fyodor Pavlovich Karamazov is a debauched, greedy father who lives a dissolute life and bears almost no sense of responsibility toward his children. He marries twice, both marriages ending tragically, and leaves his children to grow up deprived both emotionally and materially. Fyodor is not only a failure as a father but also a concentrated image of moral decay, governed by lust, selfishness, and cynical mockery.

His character becomes the catalyst that renders reconciliation within the Karamazov family impossible. He treats his children as tools or rivals, particularly in matters of money and love, pushing the father–son relationship to the brink of open hostility.

Three Sons – Three Modes of Existence

Fyodor Pavlovich’s three legitimate sons represent three distinct personality types and attitudes toward life, forming the novel’s principal ideological framework.

Dmitri Karamazov, the eldest son, embodies a life driven by instinct and emotion. He is hot-tempered, impulsive, and consumed by passion, especially in his turbulent relationship with Grushenka. Obsessed with the inheritance he believes his father has stolen from him, Dmitri harbors deep resentment toward Fyodor. Yet beneath his chaotic exterior lies a personality yearning for justice, honor, and redemption.

Ivan Karamazov, the second son, is an intellectual rationalist who represents skepticism and atheism. Ivan rejects the idea of an absolute moral order, particularly when confronted with human suffering and injustice, especially the suffering of children. His reflections on a godless world in which “everything is permitted” constitute one of the novel’s most significant philosophical axes.

Alyosha Karamazov, the youngest, is closely connected to the monastery and deeply influenced by the Elder Zosima. Alyosha embodies compassion, faith, and the capacity to listen to others. However, he is not portrayed as a symbol of absolute holiness; rather, he is a human being whose faith is continually tested by a harsh reality.

Smerdyakov – A Marginal Figure at the Center of the Tragedy

Alongside the three brothers stands Smerdyakov, Fyodor Pavlovich’s illegitimate son, raised in contempt and neglect. Taciturn and withdrawn, Smerdyakov harbors deep-seated resentment and a profound sense of inferiority. He is strongly influenced by Ivan’s ideas, particularly the rejection of absolute moral responsibility.

Though he appears to be a secondary character, Smerdyakov plays a pivotal role in the tragedy, serving as the link that transforms abstract ideas into criminal action.

Love and Money Conflicts – The Prelude to Crime

Tensions within the Karamazov family reach their peak when both Fyodor Pavlovich and Dmitri pursue Grushenka. This love triangle is not merely a romantic conflict; it exposes the father’s moral corruption and the son’s intense inner turmoil.

Simultaneously, disputes over Dmitri’s inheritance intensify. Public quarrels, impulsive threats, and Dmitri’s violent behavior lead society to view him as the most obvious suspect, possessing a clear motive for patricide.

The Murder and the Collapse of Justice

Fyodor Pavlovich is murdered under mysterious circumstances. Dmitri is swiftly arrested and brought to trial due to a series of incriminating factors: his violent past, apparent motive, and suspicious actions on the night of the crime.

Gradually, however, the truth emerges: the actual murderer is Smerdyakov, who exploits the family’s chaos and Ivan’s radical ideas to justify his deed. Ivan, though not the direct perpetrator, becomes morally complicit when he realizes that his ideas effectively granted Smerdyakov a “spiritual license” to commit murder.

Dmitri’s trial forms the novel’s dramatic climax. It does not merely judge an individual but exposes the inadequacy of human justice in confronting complex moral truths. Dmitri is convicted, while the true murderer escapes legal punishment, though not the judgment of conscience.

After the Crime – Spiritual Aftershocks

The final part of the novel focuses on the spiritual consequences of the tragedy. Ivan descends into severe psychological crisis, haunted by guilt and hallucinations. Alyosha, acting as a mediator, struggles to preserve faith in love and human responsibility amid moral ruin. Dmitri, though unjustly condemned, begins a journey of self-confrontation and reflection on redemption.

The narrative concludes without complete closure. Dostoyevsky deliberately avoids resolving the tragedy definitively, leaving readers with open questions about the nature of guilt, responsibility, and the possibility of human salvation.

3. Ideological and Artistic Value

The Brothers Karamazov is celebrated not only for its complex plot and extensive cast of characters but above all for its intellectual depth and Dostoyevsky’s transformation of the novel into a comprehensive arena of philosophical dialogue. The work’s value lies in its capacity to confront humanity with the most fundamental questions of morality, freedom, and responsibility – questions that transcend historical and cultural boundaries.

Moral Tragedy and Universal Responsibility

One of the core ideological values of The Brothers Karamazov is its redefinition of moral responsibility. Dostoyevsky does not treat responsibility merely in legal terms – who commits the crime bears the guilt – but expands it into spiritual responsibility and shared accountability among human beings.

In the Karamazov world, no one is entirely innocent. Fyodor Pavlovich creates a morally corrupt environment. Dmitri cultivates hatred and violence. Ivan disseminates ideas that negate moral limits. Smerdyakov translates these ideas into criminal action. Even Alyosha, the embodiment of faith and compassion, cannot prevent the tragedy. Crime thus ceases to be an isolated act and becomes the outcome of a systemic moral collapse.

The principle that “everyone is guilty before everyone else” becomes the novel’s ethical axis, directly challenging the human tendency to evade responsibility by assigning blame to others.

Faith, Doubt, and the Paradox of Freedom

A major intellectual contribution of The Brothers Karamazov lies in its treatment of faith and doubt as equal interlocutors, without imposing a final resolution. Dostoyevsky does not construct a world in which faith triumphs effortlessly; instead, he subjects it to relentless challenges posed by reason and human suffering.

Through Ivan’s character and the legend of the Grand Inquisitor, the novel poses a fundamental question: do human beings truly desire freedom, or are they willing to sacrifice it for security and order? Here, freedom is not romanticized but understood as a psychological burden. Once granted absolute freedom, individuals must also bear the corresponding moral consequences.

Dostoyevsky demonstrates that freedom divorced from responsibility leads not to liberation but to nihilism and violence, anticipating core ideas later developed in existentialist philosophy.

Humanistic Value and the View of Humanity

Despite placing human beings in extreme circumstances, The Brothers Karamazov does not deny the possibility of redemption. Dostoyevsky does not view humanity as irrevocably condemned to evil but as constantly oscillating between moral downfall and the aspiration toward goodness.

Dmitri, despite his flaws, retains the capacity for repentance. Ivan, though mentally shattered, cannot escape the call of conscience. Alyosha, though powerless in the face of tragedy, continues to serve as a connective force, sustaining faith in love among human beings. The novel’s humanistic value lies in its affirmation that people lose themselves only when they reject responsibility and love for others.

Polyphonic Narrative and Ideological Dialogue

Artistically, The Brothers Karamazov stands as a quintessential example of the polyphonic novel. Dostoyevsky does not impose an omniscient voice but allows characters to articulate their worldviews through dialogue, debate, and conflict.

Each character participates not only in the plot but also in an ongoing ideological debate. Lengthy dialogues – especially between Ivan and Alyosha – do not slow the narrative but generate intense intellectual tension. Literature here becomes not merely a storytelling medium but an instrument of thought.

Furthermore, the psychological portrayal reaches remarkable subtlety. Internal monologues, mental breakdowns, and hallucinations reflect not only personal crises but also the collapse of value systems when human beings are severed from moral foundations.

The Enduring Value of the Work

The enduring value of The Brothers Karamazov – Dostoyevsky does not lie in providing definitive answers but in its capacity to place readers in a continual state of self-questioning. The novel retains its relevance in the modern world, where concepts of truth, faith, and personal responsibility remain deeply contested.

Its openness of thought, profound analysis of human nature, and complex artistic structure allow The Brothers Karamazov to transcend its historical context and stand as one of the most enduringly significant works of world literature.

4. Notable Quotations

One reason The Brothers Karamazov is regarded as a philosophical masterpiece lies in its language, rich in intellectual argumentation. Dostoyevsky avoids ornamental prose; the power of the work emerges from direct, often intellectually provocative statements that compel readers to reconsider the foundations of morality and belief.

The following quotations not only represent individual characters’ perspectives but also encapsulate the novel’s central questions concerning God, freedom, responsibility, and the human capacity for love.

- “If God does not exist, then everything is permitted.”

A statement associated with Ivan Karamazov, expressing the ultimate logic of moral atheism and challenging the very foundation of ethical order. - “We are all responsible for all, before everyone.”

This idea redefines guilt as collective responsibility, where indifference itself becomes a form of complicity. - “Man cannot live by bread alone.”

This line highlights the conflict between material needs and spiritual life, affirming that physical sustenance cannot replace the search for meaning. - “Love in action is a harsh and dreadful thing compared with love in dreams.”

Dostoyevsky distinguishes idealized love from love rooted in responsibility and concrete action. - “Nothing has ever been more unbearable for man and human society than freedom.”

Freedom appears not as pure liberation but as a psychological burden demanding moral accountability. - “People often prefer to surrender freedom in exchange for peace.”

Through the Grand Inquisitor legend, Dostoyevsky exposes the paradox of humanity’s relationship with freedom. - “Hell is not fire, but the suffering of no longer being able to love.”

Punishment is relocated from the metaphysical realm to the inner spiritual condition of the individual. - “No one can escape their own conscience.”

Even when social justice fails, conscience remains an absolute inner tribunal. - “God’s silence is not denial, but a test.”

Faith is presented not as certainty, but as a journey marked by doubt and choice.

These quotations demonstrate that The Brothers Karamazov does not deliver a single moral message. Instead, each statement opens a field of reflection, compelling readers to establish their own positions on the fundamental questions of human existence.

5. Conclusion

The Brothers Karamazov – Dostoyevsky stands as one of the rare novels in world literature that achieves a complete synthesis of intellectual depth and artistic power. Through the tragedy of the Karamazov family, the work transcends a narrative of crime and judgment to become a forum for dialogue on the most fundamental aspects of human life: faith, freedom, responsibility, and the capacity to love.

In terms of content, the novel places human beings in extreme moral situations, where every decision carries unavoidable consequences. Dostoyevsky does not excuse or rationalize evil; instead, he traces it to the collapse of moral foundations and the evasion of personal responsibility. This approach elevates The Brothers Karamazov beyond the boundaries of a crime novel into a profound inquiry into human nature under spiritual crisis.

Artistically, the novel demonstrates mastery in character construction, ideological dialogue, and psychological depiction. Its polyphonic structure allows multiple moral and philosophical positions to coexist, confront, and negate one another, producing an open text resistant to definitive conclusions. This quality has ensured the work’s lasting scholarly relevance and continual reinterpretation.

Within the broader scope of Dostoyevsky’s literary career, The Brothers Karamazov may be regarded as his most comprehensive intellectual summation, where his deepest concerns about humanity and society are explored to their fullest extent. By posing foundational questions without sacrificing literary vitality, the novel secures its place as one of the most important achievements in world literature and continues to exert profound intellectual influence in the modern era.