In the history of modern Japanese manga, only a small number of works have managed to transcend the boundaries of entertainment to become global intellectual phenomena. Attack On Titan (Shingeki no Kyojin) by Hajime Isayama stands as a representative example of such a transformation. Emerging at a time when shōnen manga was gradually becoming saturated with familiar heroic narratives and triumphant resolutions, Attack On Titan appeared as a radical rupture – darker, more violent, and far more reflective than the conventional norms of mainstream comics.

Rather than merely recounting a survival battle between humanity and giant Titans, Attack On Titan steadily expands its narrative scope, evolving from a post-apocalyptic fantasy into a tragic epic about history, war, and freedom. The world of the series is constructed as a microcosm of human society, where fear, hatred, and collective memory shape individual behavior and determine the fate of entire communities. This narrative shift elevates Attack On Titan beyond the status of an ordinary manga, positioning it as a text rich in philosophical and political depth.

On a broader level, Attack On Titan vividly reflects modern humanity’s anxieties surrounding violence, nationalism, historical repetition, and the paradoxical nature of freedom. The work offers no simple answers, nor does it construct its characters along clear-cut lines of good and evil. Instead, it persistently confronts readers with morally ambiguous choices and irreversible consequences. It is precisely this approach that has allowed Attack On Titan to become one of the most influential manga of the early twenty-first century, while also opening new pathways for Japanese comics to engage with global and humanistic concerns.

1. Introduction to the Author and the Work

Hajime Isayama, born in 1986 in Ōita Prefecture, Japan, is one of the most prominent manga artists of the new generation. He is distinguished not only by his imaginative world-building but also by his ability to engage with historical, political, and philosophical issues through the medium of manga. Lacking formal training from prestigious art institutions, Isayama faced repeated rejections early in his career due to a drawing style that did not conform to mainstream commercial standards. However, it was precisely this roughness in line work and character depiction that later contributed to the heavy, brutal, and realistic atmosphere that became an irreplaceable hallmark of Attack On Titan.

Attack On Titan (Shingeki no Kyojin) officially debuted in 2009 in Bessatsu Shōnen Magazine, published by Kodansha. At a time when the shōnen manga market favored optimistic narratives emphasizing teamwork and victory, Attack On Titan immediately distinguished itself through its bleak worldview, where death, defeat, and loss are portrayed directly and without evasion. This contrast quickly drew the attention of younger readers while also provoking intense debate among manga critics.

Structurally, Attack On Titan was conceived by Isayama as a long-term narrative project. Elements related to history, politics, ethnicity, and collective memory are embedded from the earliest chapters, only revealing their full significance in later stages of the story. Spanning more than a decade (2009–2021) and comprising 34 volumes, the series reflects the increasing complexity of Isayama’s creative thinking and his growing narrative ambition.

Isayama has acknowledged influences from a wide range of sources, including European war history, Western dystopian literature, and harsh survival narratives. These influences are transformed into a highly symbolic world within Attack On Titan, where the walls function not merely as physical defenses but as representations of fear, isolation, and the psychological limitations humanity imposes upon itself.

The overwhelming success of Attack On Titan is measured not only by its global sales figures, reaching tens of millions of copies, but also by its extensive adaptations into anime, films, games, and other media forms. The anime adaptation in particular played a decisive role in expanding the series’ global reach, establishing Hajime Isayama as a defining figure in contemporary Japanese manga.

Within the broader history of manga, Attack On Titan is regarded as a significant milestone, marking a clear shift from traditional heroic adventure stories toward works with deeper intellectual engagement that confront the darker realities of human society. This transformation has secured a distinctive position for both Hajime Isayama and Attack On Titan, not only among readers but also within critical and academic discourses on modern comics.

2. Summary of the Plot

The setting of Attack On Titan is a world in which humanity appears to stand on the brink of extinction. The survivors are forced to live behind three massive walls – Maria, Rose, and Sina – to protect themselves from the Titans, gigantic humanoid creatures characterized by overwhelming size, brutal behavior, and mysterious origins. For over a century, these walls serve not only as defensive structures but also as symbols of social order, false stability, and the belief that the outside world contains nothing but death.

The story begins with a pivotal catastrophe when the Colossal Titan and the Armored Titan breach Wall Maria, leading to the collapse of part of humanity’s territory. This disaster results in massive loss of life and shatters the illusion of safety behind the walls. In this context, Eren Yeager, alongside Mikasa Ackerman and Armin Arlert, joins the military with the initial goal of exterminating the Titans and reclaiming freedom for humanity.

In its early stages, Attack On Titan functions as a military survival narrative, focusing on brutal training, bloody battles, and the continuous sacrifice of human lives in the face of an overwhelmingly powerful enemy. Yet from the outset, the series plants seeds of instability within its world: Titans exhibiting abnormal behavior, secrets concealed by those in power, and, most notably, the emergence of Titans possessing human intelligence.

A major turning point occurs when Eren discovers his ability to transform into a Titan. This revelation completely overturns previous assumptions about the boundary between humanity and its enemy, opening a series of questions concerning the origins of the Titans, the nature of power, and the role of memory. From this point onward, Attack On Titan gradually abandons simple oppositional storytelling in favor of a far more complex narrative structure, where characters, motivations, and objectives are constantly redefined.

As the story progresses, the secrets hidden in the Yeager family basement and the truth about the world beyond the walls are revealed. Humanity is no longer portrayed as the ultimate victim of the Titans, but rather as one part of a long – standing historical conflict between nations and ideologies. The narrative scope expands to a global scale, introducing opposing political systems and factions, thereby exposing the origins of hatred and violence transmitted across generations.

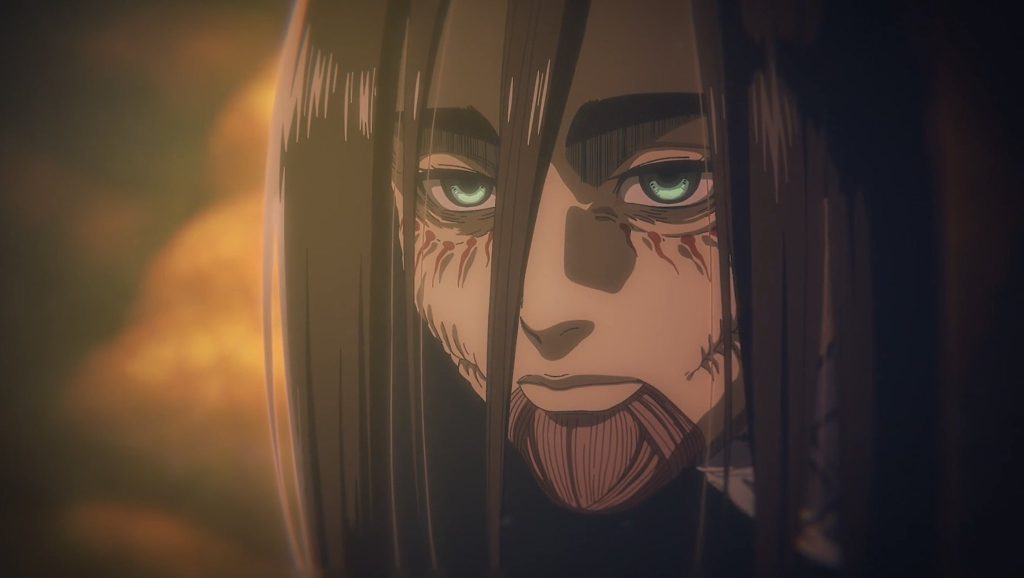

In its final stages, the narrative centers on the ideological transformation of Eren Yeager. Once a boy driven by a longing for freedom, Eren becomes the central figure behind the Rumbling, a genocidal catastrophe intended to destroy the outside world in order to protect his homeland. This choice is not presented as heroic, but as an inevitable consequence of history, memory, and inescapable cycles of violence.

Through the journey of Eren and his companions, Attack On Titan concludes as a tragic epic devoid of absolute victory. The story closes by raising open-ended questions about responsibility, freedom, and the cost of peace rather than offering definitive answers. It is this narrative design that has made Attack On Titan one of the most complex and contemplative manga in the history of Japanese comics.

3. Themes and Ideological Foundations

3.1 Freedom and the Paradox of Liberation

In Attack On Titan, “freedom” is not presented as a clear destination but as a deeply contradictory and paradoxical concept. From the earliest chapters, freedom is associated with the world beyond the walls – an open space unclaimed by fear. However, as the narrative deepens, this concept grows increasingly complex, as every attempt to break free from confinement results in new, more insidious forms of imprisonment.

Eren Yeager stands at the center of this ideological axis. His journey demonstrates that freedom is constrained not only by external forces but also by memory, destiny, and predetermined choices. Attack On Titan thus poses a fundamental question: can humans truly be free if their actions are shaped by history and circumstance, or is freedom merely an illusion that sustains the cycle of violence?

3.2 War, Hatred, and the Cycle of History

One of the core ideas in Attack On Titan is the portrayal of war as an endlessly repeating process. Conflict in the series does not originate from isolated individuals but from collective memories passed down through generations. Hatred, in the world of Attack On Titan, does not arise spontaneously; it is cultivated through education, propaganda, and the distortion of historical truth.

Isayama deliberately avoids constructing factions according to absolute moral binaries. Each side of the conflict carries its own historical trauma, existential fears, and justifications. This moral relativism brings the depiction of war in Attack On Titan closer to real human history, where violence is often rationalized in the name of survival or justice.

By exposing the mechanisms through which hatred operates, Attack On Titan confronts readers with a stark reality: wars do not end with victory but merely pause in preparation for the next cycle of conflict.

3.3 Power, Memory, and the Manipulation of History

Another crucial ideological theme in Attack On Titan is the relationship between power and memory. The power of the Titans is not merely military; it is also tied to the ability to control, alter, and reconstruct human memory. Through this element, Isayama demonstrates that history is not an objective sequence of events but a product of selective remembrance, concealment, and interpretation by those in power.

In the world of Attack On Titan, controlling memory equates to controlling identity and collective perception. This dynamic mirrors the functioning of totalitarian societies, where truth is manipulated to maintain order and legitimize violence. The work thereby raises questions about individual responsibility when confronting history: is one obligated to seek truth, or to accept a convenient narrative in order to survive?

3.4 Human Nature and the Fragility of Morality

Attack On Titan approaches humanity as an inherently contradictory existence – capable of empathy yet easily driven toward violence when pushed to extremes. In situations of absolute survival, moral standards rapidly erode, giving way to pragmatic and often ruthless decisions.

Rather than offering simplistic moral judgments, the series situates its characters within moral gray zones shaped by choice and consequence. Through this approach, Isayama illustrates that morality is not an immutable system of values but one profoundly influenced by historical context, power structures, and collective fear. This fragility of ethics intensifies the tragic weight of Attack On Titan.

3.5 The Individual and Historical Responsibility

Beyond these themes, Attack On Titan also explores the complex relationship between the individual and history. Characters in the series – whether wielding immense power or remaining ordinary individuals—are unable to escape the broader currents of historical movement. Individual choices, when accumulated and intertwined, generate collective upheaval.

The message suggested by Attack On Titan does not lie in glorifying or diminishing individual agency, but in emphasizing the responsibility that accompanies power and choice. When history is written through human action, no decision exists without long-lasting consequences.

4. Value and Influence

4.1 Artistic Value and Narrative Structure

From an artistic standpoint, Attack On Titan is highly regarded for its long-term narrative vision and precise control of pacing. Rather than following a simple linear model, the series continuously expands and restructures its worldview through layers of information introduced early and reinterpreted later. Details that initially appear fragmented are gradually interconnected, creating powerful retrospective effects that deepen the overall narrative.

Isayama’s use of narrative “twists” does not rely on shock value alone but functions as a mechanism for redefining prior events. Each major turning point compels readers to reassess their understanding of the world, characters, and motivations, elevating the reading experience from passive consumption to active reflection.

4.2 Visual Style and Expressive Language

The art style of Attack On Titan has often been debated for deviating from conventional manga aesthetics. Yet its rough, angular, and occasionally unbalanced visuals contribute significantly to the tense, brutal, and anti-heroic atmosphere of the series. Combat scenes, expressions of pain, and depictions of destruction are rendered directly and without restraint, aligning with the work’s uncompromising realism.

The visual language of Attack On Titan is highly symbolic. From the walls and Titans to urban spaces and battlefields, these elements function not merely as settings but as vehicles of meaning, enabling the series to communicate its ideas beyond dialogue and into a rich visual discourse.

4.3 Ideological Value and Reflective Depth

The greatest value of Attack On Titan lies in its capacity to pose foundational questions about humanity and society. The work avoids delivering clear moral messages or imposing a single interpretation, instead forcing readers to confront difficult issues such as war, genocide, nationalism, and historical responsibility.

This refusal to simplify has established Attack On Titan as a deeply reflective text suitable for interdisciplinary analysis. Readers may approach it through political philosophy, sociology, or memory studies, thereby expanding the recognition of manga as a serious artistic medium.

4.4 Cultural Impact and the Globalization of Manga

In terms of influence, Attack On Titan is one of the few manga to achieve global success on both commercial and academic levels. Its anime adaptation introduced the series to a vast international audience, reinforcing the position of Japanese manga within global popular culture.

The imagery, symbolism, and themes of Attack On Titan have permeated various cultural domains, including music, film, fashion, academic discourse, and social media. The work has become a critical reference point in discussions surrounding dark, mature, and politically engaged manga of the twenty-first century.

4.5 Impact on the Manga Industry and Contemporary Creation

Attack On Titan is widely regarded as a pivotal moment in the evolution of shōnen manga. It demonstrated that youth-oriented comics can successfully engage with complex and controversial themes while maintaining widespread appeal. This achievement paved the way for subsequent works to explore deeper social and ideological issues.

The influence of Attack On Titan extends beyond content to how younger creators perceive manga as a medium for intellectual expression. Within the contemporary comics landscape, the series has helped redefine the boundary between entertainment and art, between popular appeal and scholarly inquiry.

5. Conclusion

Attack On Titan is not merely a commercially successful manga or a technically accomplished narrative, but a work driven by clear intellectual ambition. Through a harsh and conflict-ridden fictional world, Hajime Isayama constructs a profound discourse on freedom, war, memory, and historical responsibility. The series does not seek to provide easy entertainment or immediate emotional gratification, but persistently challenges readers with difficult questions that resist definitive answers.

The distinctive strength of Attack On Titan lies in its rejection of simplistic moral binaries. Characters, regardless of their position within the conflict, are situated within specific historical contexts where individual choices are shaped by collective memory and power structures. This approach allows the work to authentically depict the complexity of human nature and highlight the fragility of moral frameworks under the pressure of violence and survival.

On a broader scale, Attack On Titan represents a major turning point in the development of contemporary Japanese manga. It demonstrates that popular comics can serve as a platform for engaging with global issues such as nationalism, war, historical cycles, and the paradox of freedom. Consequently, the influence of Attack On Titan extends beyond entertainment into academic research, critical discourse, and social reflection.

As the narrative concludes, Attack On Titan leaves behind a legacy defined more by debate than consensus. The work offers no final answers and makes no attempt to reconcile all of its contradictions. Instead, its enduring value lies in its ability to stimulate critical thinking and sustain long-term dialogue about humanity and history. It is this capacity that secures Attack On Titan a place among the most significant and intellectually profound manga of the twenty-first century.