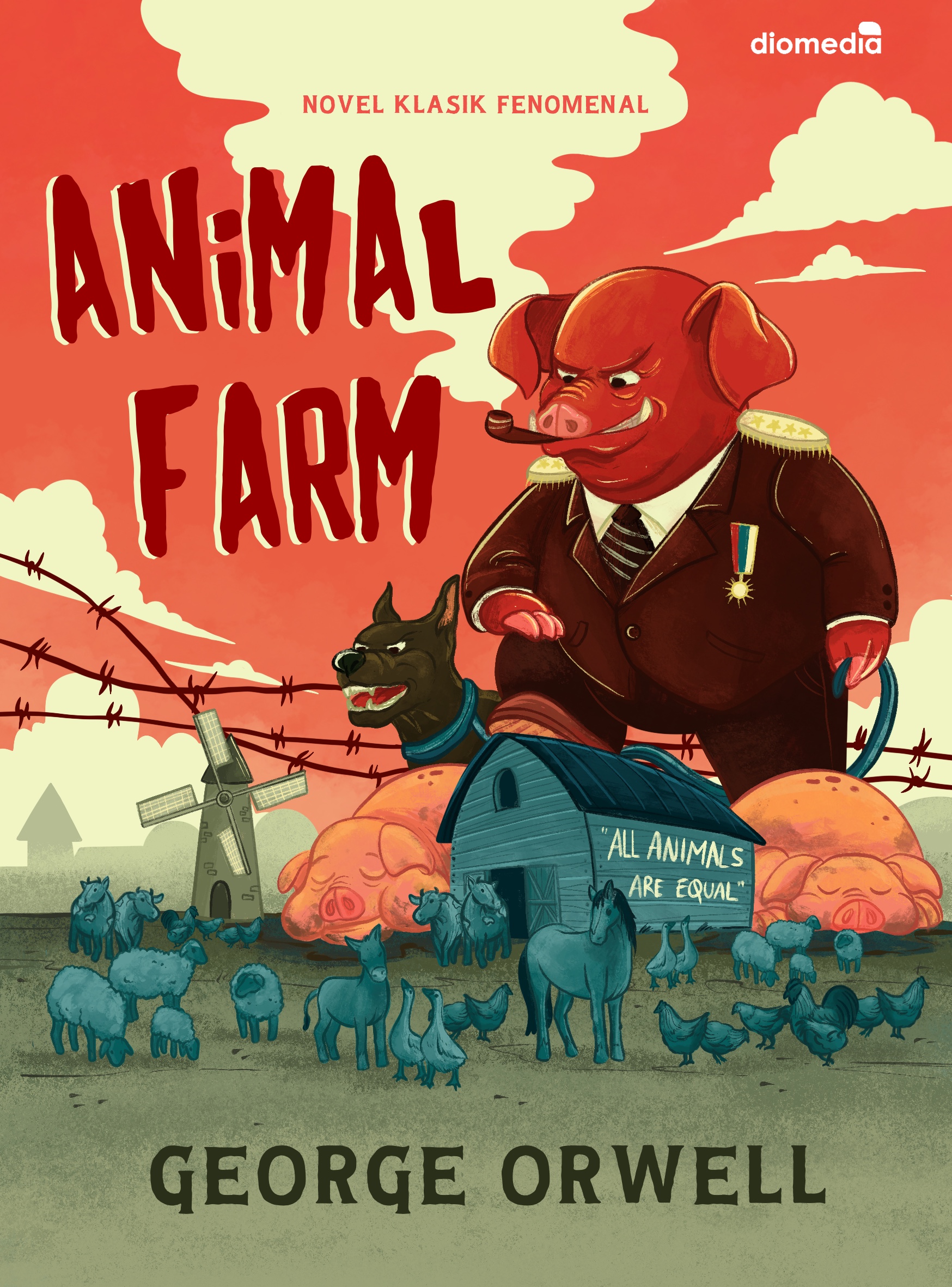

In the flow of world literature in the twentieth century, few works of such modest length possess an ideological impact as profound and enduring as Animal Farm. Through what appears to be a simple allegorical tale about animals on a farm, the novel opens up a sharply critical political space in which power, ideals, and moral degeneration are stripped down to their very core. Without resorting to explicit argumentation or heavy theoretical discourse, Animal Farm chooses a clear and straightforward narrative style, yet beneath this apparent simplicity lies a dense and haunting system of symbols.

First published in 1945, the work quickly transcended its specific historical context to become a text of universal significance. It tells the story of how a revolution, initiated in the name of freedom and equality, is gradually betrayed from within. For that reason, Animal Farm is not merely a political novel, but also a lasting warning about power, the credulity of the masses, and the manipulation of language in social life.

1. The Author and the Work

The author of Animal Farm is George Orwell (1903–1950), whose real name was Eric Arthur Blair – one of the most influential writers, journalists, and political thinkers in twentieth-century English literature. Orwell is known not only as a novelist but also as a sharp political essayist who devoted almost his entire career to examining the nature of power, truth, and individual freedom in modern society.

Orwell’s life was closely bound to direct experiences of injustice and oppression. He once served in the British colonial police in Burma, where he personally witnessed the harsh mechanisms of imperial rule. This experience planted in him a deep skepticism toward all forms of imposed authority. Later, he spent many years living in poverty, taking on various manual jobs in Paris and London, which enabled him to understand the lives of those pushed to the margins of society. These experiences became the realistic foundation for his humanistic yet deeply vigilant worldview.

Politically, Orwell identified himself as a democratic socialist, but he firmly opposed totalitarianism in all its forms. What set him apart was his intellectual independence: he idolized no system and refused to sacrifice individual freedom and truth for abstract ideals. Consequently, his works often carry a tone that is sober, cold, and at times biting, yet always oriented toward the defense of human dignity.

Animal Farm was written in the final years of World War II and published in 1945, a moment when the world had begun to reflect on the consequences of revolutions and political systems carried out in the name of liberation. The novel is a political allegory that uses the image of animals on a farm to represent the process by which a revolution becomes distorted from within. Although clearly inspired by the Russian Revolution and the subsequent emergence of a totalitarian regime, Orwell did not confine his work to a mere historical allegory. Instead, he constructed Animal Farm as a miniature model of society, in which the mechanisms of power, propaganda, and obedience are presented in a universal form.

What distinguishes Animal Farm is its mode of expression. Orwell adopts a simple narrative style, almost resembling a children’s story, yet beneath this transparent surface lies a tightly organized ideological structure and a powerful warning. Each character and each event carries clear symbolic meaning, but never in a rigid or didactic way. Readers can approach the work on multiple levels: as an accessible fable, as a sharp political critique, or as a study of mass psychology and the manipulation of language.

It is precisely this harmonious combination of penetrating thought and restrained storytelling that has allowed Animal Farm to transcend its era and become a classic. The novel does not merely reflect a particular historical moment; it raises enduring questions about how power is granted, how truth is distorted, and how lofty ideals can be quietly yet thoroughly betrayed.

2. Summary of the Plot

The story of Animal Farm takes place on Manor Farm, where the animals live under the rule of Mr. Jones, a human who represents the old ruling class: lazy, irresponsible, and concerned only with exploiting the labor of others. In this context, the lives of the animals are dominated by hunger, hard work, and prolonged injustice. It is precisely this suffocating reality that creates the conditions for revolutionary ideas to emerge.

The origin of the revolution is the speech delivered by Old Major, an aged and respected boar known for his wisdom and experience. At a nighttime meeting, Old Major exposes the exploitative nature of human rule and evokes a vision of an ideal society in which animals would control their own destiny. He asserts that all their suffering stems from humans, and that only by overthrowing mankind can freedom and equality become a reality. This speech functions not only as a call to rebellion, but also as the ideological foundation for all the events that follow.

After Old Major’s death, his revolutionary ideas are continued and systematized by the two most intelligent pigs, Snowball and Napoleon. They transform his initial vision into a doctrine called “Animalism,” codified in the Seven Commandments written on the barn wall, which emphasize absolute equality among animals and hostility toward humans. At this stage, the animals still maintain a sense of unity and faith in a shared future.

The rebellion itself occurs quickly and almost spontaneously when Mr. Jones, in a drunken stupor, neglects the farm. The animals rise up together and drive Jones and his men away. This victory marks the birth of Animal Farm – a space seemingly liberated from oppression. In the early days after the revolution, the atmosphere is filled with hope: labor is organized more fairly, productivity increases, and the animals believe that the fruits of their work finally belong to themselves.

However, the first cracks soon appear within the leadership. Snowball and Napoleon repeatedly clash, particularly over the plan to build a windmill, a symbol of progress and long-term prosperity. Snowball represents reformist thinking, emphasizing education and collective participation, while Napoleon remains reserved and quietly accumulates power. The conflict reaches its climax when Napoleon uses a pack of dogs he has secretly trained to expel Snowball from the farm, completely eliminating all opposition.

From that moment on, Animal Farm enters a period of unmistakable degeneration. Napoleon proclaims himself the supreme leader and rules through violence, propaganda, and fear. Decisions are no longer made in common assemblies; instead, all orders come from Napoleon and are conveyed by Squealer, the pig who specializes in manipulating language. Squealer constantly distorts the truth, persuading the animals that their current hardships are necessary and that Snowball is a dangerous enemy plotting to destroy the farm.

Alongside the concentration of power is the subtle alteration of the Commandments. One by one, they are modified, supplemented, or reinterpreted to suit the pigs’ interests. The other animals, lacking education and the ability to remember clearly, gradually accept these changes as natural. Truth is rewritten, history is falsified, and memories of the early days of the revolution fade into obscurity.

The character of Boxer, the strong, hardworking, and loyal cart – horse, becomes a symbol of the exploited working class. With his absolute faith in the slogan “Napoleon is always right” and his personal motto “I will work harder,” Boxer devotes all his strength to the farm without ever questioning authority. When he becomes exhausted and can no longer work, he is cruelly sold off, exposing the blatant betrayal of the new regime toward those who had sacrificed the most for the revolution.

In the final scene of the novel, the boundary between pigs and humans completely disappears. Napoleon and the pigs begin to walk on two legs, wear clothes, drink alcohol, and socialize with humans – those who were once regarded as mortal enemies. The last remaining commandment on the wall is reduced to a single sentence that encapsulates the entire absurdity of power: “All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others.” The other animals look from pig to man and from man to pig, and can no longer tell which is which. The revolution thus ends in a cruel cycle, in which the old oppressors are replaced by a new power even more oppressive and more insidious.

3. Thematic and Artistic Value

Thematic Value: The Nature of Power and the Betrayal of Ideals

The central ideological value of Animal Farm lies in its exposure of the inevitable corruption of power when it is left unchecked. George Orwell does not portray power as inherently evil from the outset; rather, he shows that it is often granted with the most noble expectations: freedom, justice, and liberation. The animals’ uprising springs from legitimate aspirations, driven by shared suffering and faith in a better society. Yet it is precisely this naïve faith that opens the way to tragedy.

The novel raises a fundamental issue: revolutions do not usually fail because of external enemies, but collapse from within. As power gradually becomes concentrated in the hands of a small group – in this case, the pigs – the original principles are first adjusted, then distorted, and finally completely replaced. Orwell demonstrates that betrayal does not occur abruptly, but proceeds quietly, step by step, until the moment of realization comes too late. This is what makes Animal Farm so unsettling: evil does not appear in a violent and obvious form, but in the guise of reasonableness, necessity, and actions taken “for the common good.”

Another important theme of the work is the credulity and passivity of the masses. Most of the animals are not subdued primarily by physical force, but by ignorance and the habit of obedience. They accept hunger and hardship because they are convinced that such sacrifices are necessary to ward off an imagined enemy. The character of Boxer is the clearest embodiment of this tragedy: hardworking, absolutely loyal, yet never questioning. Through him, Orwell criticizes not only the rulers, but also those who are ruled, when they relinquish their capacity for independent thought and critical judgment.

In addition, Animal Farm serves as a powerful warning about the manipulation of language. Concepts such as “equality,” “sacrifice,” and “enemy” are employed as tools to shape perception. When language is distorted, truth is no longer something to be verified, but something to be “explained away.” This is one of the novel’s most significant intellectual contributions: the insight that control over language is, in essence, control over thought itself.

Artistic Value: Modern Allegory and the Art of Restraint

Artistically, Animal Farm stands as a remarkable example of the power of the modern allegorical form. Orwell’s choice to tell a political story through animals may appear simple, but it proves extraordinarily effective. It allows the work to avoid overt didacticism while at the same time broadening its audience: readers of different ages, educational backgrounds, and cultural contexts can all approach the story in their own way.

The system of symbols in the novel is consistent yet never rigid. The characters are not mechanical replicas of specific historical figures, but rather represent types of people and forms of power with universal relevance. For this reason, Animal Farm is not confined to a single period or political regime, but retains its immediacy and applicability across time.

Orwell’s prose style is another crucial artistic element. He employs simple, direct language and short, restrained sentences, minimizing overt emotional coloring. There are no elaborate descriptions or intrusive authorial judgments. This very coolness, however, intensifies the ideological impact, compelling readers to reflect for themselves rather than being guided by overt emotional cues. This is characteristic of Orwell’s style: the less he judges, the more clearly the message emerges.

The structure of the narrative is also carefully organized according to the stages of a revolution: the formation of ideals, the seizure of power, the concentration of authority, corruption, and the reestablishment of oppression. Each stage contains its own climax and consequences, making the story function as a miniature social model. Thanks to this structure, Animal Farm is not merely a story, but a conceptual map of how power operates.

One of the reasons Animal Farm has become a classic lies in its system of short sentences that nevertheless carry immense ideological weight. George Orwell does not rely on lengthy philosophical statements, but allows slogans, commandments, and seemingly simple remarks to reveal the absurdity and cruelty of power. At each stage of the story, these quotations not only reflect the reality unfolding in the farm, but also demonstrate the progressive deformation of language, thought, and morality.

From the very beginning, the revolutionary ideal is condensed into what appears to be an absolute belief:

“All animals are equal.”

This slogan marks the symbolic birth of Animal Farm, representing the original and pure aspiration for justice. At the moment of its appearance, it carries the meaning of liberation, awakening faith and solidarity throughout the community.

However, this ideal is soon replaced by a deeply paradoxical variation:

“All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others.”

This sentence stands as the pinnacle of linguistic corruption. By placing two contradictory clauses side by side, power legalizes injustice and transforms absurdity into a new norm. It is also the quotation that crystallizes the entire critical spirit of the novel.

During the revolutionary process, simple slogans are used to extinguish critical thinking:

“Four legs good, two legs bad.”

This formula divides the world into two clearly opposed camps, eliminating all shades in between. It demonstrates how binary thinking is exploited to oversimplify reality and direct the masses.

Blind obedience is reinforced through personalized belief:

“Napoleon is always right.”

This statement reflects the psychology of leader worship, in which truth no longer rests on reason or reality, but on the will of the one who holds power.

To sustain domination, fear is continuously cultivated:

“If the animals do not want Jones to come back, they must obey Napoleon.”

Here, authority no longer needs to prove its legitimacy; it merely needs to invent a threat in order to force others to choose the “lesser evil.”

Control extends not only to the present, but also to collective memory:

“Who controls the past controls the future; who controls the present controls the past.”

This quotation reveals the central role of rewriting history. When memory is manipulated, the possibility of resistance is also erased.

The commandments – symbols of revolutionary morality – are subtly twisted:

“No animal shall sleep in a bed… with sheets.”

The addition of just a few words completely alters the meaning of the rule, illustrating how power operates through seemingly harmless adjustments.

Violence, too, is legitimized through language:

“No animal shall kill any other animal… without cause.”

This line exposes the danger of attaching moral conditions to acts of violence, turning crime into something acceptable.

Finally, the harsh reality of the oppressed class is captured in a cold and simple truth:

“The animals worked harder than ever, but their rations grew smaller.”

This is a sentence without slogans or ideals, reflecting nakedly the exploitative essence of the new regime.

And the image that closes the novel is among the most haunting passages in world literature:

“The animals looked from pig to man, and from man to pig, and from pig to man again; but already it was impossible to say which was which.”

This sentence marks the complete collapse of moral boundaries and ideals, affirming that the cycle of oppression has returned to its starting point.

5. Conclusion

With its concise length yet tightly constructed ideological framework, Animal Farm firmly establishes itself as one of the most representative political and social works of twentieth – century literature. Through the seemingly simple form of an allegory, George Orwell constructs a miniature model of society in which the formation, operation, and corruption of power are presented with clarity, logic, and haunting force. The revolution in the novel does not collapse because of external enemies, but disintegrates through the betrayal of ideals by those who claim to act in the name of liberation.

The enduring value of Animal Farm lies in its universality. Although written in a specific historical context, the work is not confined to any particular era or political system. The issues Orwell raises – the manipulation of language, the cult of power, the passivity of the masses, and the danger of losing freedom in the name of equality – remain powerful warnings for modern society. The novel compels readers to confront an uncomfortable truth: oppression is not sustained solely by those who rule, but is also nourished by the credulity and silence of those who are ruled.

Artistically, Animal Farm demonstrates the strength of restrained writing. Without resorting to direct proclamations or heavy moral judgment, the work allows the unfolding of events and the system of symbols to speak for themselves. The simplicity of language, combined with a tightly organized structure and a calm, lucid narrative voice, renders its message all the more sharp and unforgettable.

From an overall perspective, Animal Farm is not merely a book to be read, but a text that deserves to be reread and reflected upon many times. It does not offer ready-made solutions to social problems, but instead poses fundamental questions about power, responsibility, and critical thinking. It is precisely in this capacity to awaken awareness that the novel proves its lasting value in world literature and human thought.