Not many literary works can make readers laugh out loud and then fall silent in reflection about the way they themselves are living. Don Quixote is such a book. Beneath its seemingly comic situations and misguided adventures lies a profound story about the human condition when confronted with reality – a world in which lofty ideals constantly collide with the harsh limits of everyday life.

Born in a period when European society was undergoing a profound transition from the medieval world to the early modern age, Don Quixote does more than depict the decline of the chivalric spirit. It captures a moment when human beings began to develop a deeper awareness of the individual self, of loneliness, alienation, and the enduring desire to search for meaning in existence. The aging knight Don Quixote, armed with an absolute faith in justice and honor, walks through a world that no longer has room for such values, becoming a figure who is at once laughable and deeply pitiable.

Reading Don Quixote today, modern readers can easily recognize fragments of themselves within its story: between once-beautiful dreams, growing skepticism, and the constant tension between “living realistically” and “living according to one’s beliefs.” The contrast between the dreamy Don Quixote and the pragmatic Sancho Panza is not merely a literary device, but a metaphor for the two forces that coexist within every human being.

For this reason, Don Quixote is not simply a classical novel to be read out of obligation, but a work capable of sustaining a lasting dialogue with readers across generations. The more closely one reads it, the more one feels questioned, unsettled, and compelled to reflect on the meaning of ideals, failure, and what it truly means to be human in an ever – changing world.

1. Introduction to the Author and the Work

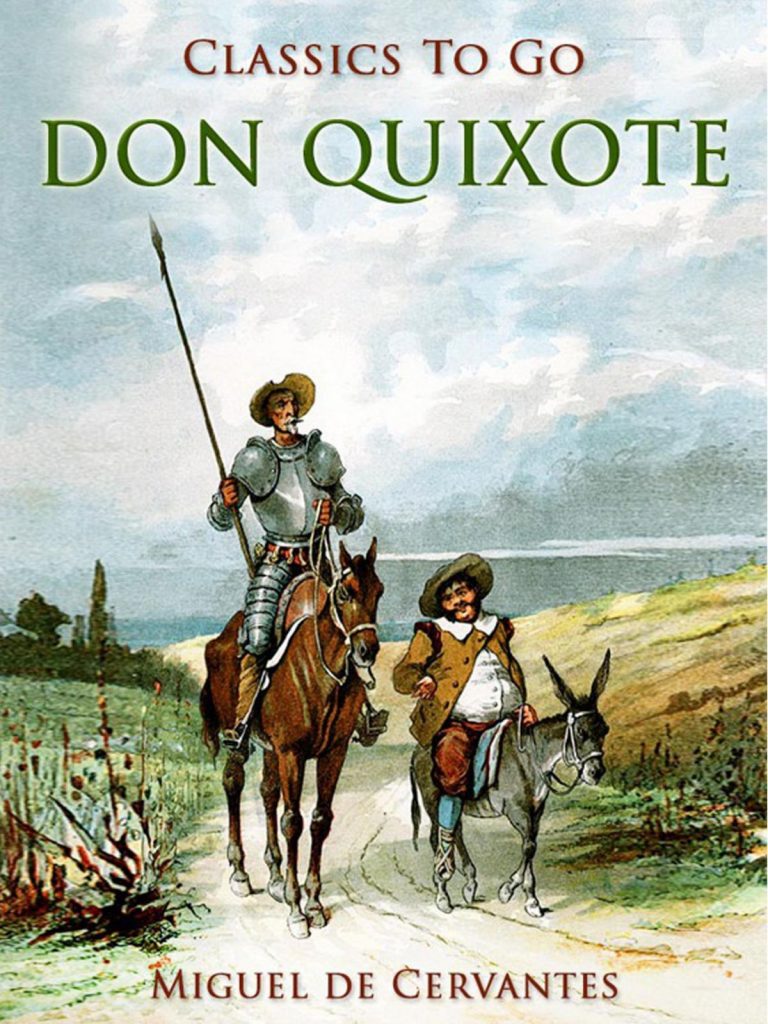

The author of Don Quixote is Miguel de Cervantes (1547–1616), the greatest writer of Spain and one of the most influential figures in the history of world literature. Cervantes’ life was far from smooth or glorious, unlike that of many other literary geniuses. He was once a soldier, fought in the famous Battle of Lepanto, and suffered severe injuries. Later, he was captured by pirates and imprisoned for many years in North Africa. Upon returning to his homeland, Cervantes continued to live in poverty and instability, and was repeatedly imprisoned due to financial difficulties.

These bitter experiences and constant confrontations with reality shaped Cervantes into a writer with a penetrating, lucid, yet ultimately compassionate view of humanity. His literature neither idealizes the world nor completely rejects idealism. Instead, it consistently places human beings in a state of tension between dreams and reality, between noble aspirations and the unforgiving constraints of life.

Don Quixote (full title: El ingenioso hidalgo Don Quijote de la Mancha) was published in two parts, in 1605 and 1615 respectively. From the moment it appeared, the novel attracted widespread attention and was enthusiastically received by readers throughout Europe. Initially, it was regarded primarily as a satirical work mocking the outdated chivalric romances that had dominated the late medieval period. Over time, however, critics came to recognize that beneath its humorous surface lay a complex novelistic structure and a humanistic vision that far surpassed mere parody.

Today, Don Quixote is widely regarded as one of the foundational works of the modern novel, where characters are no longer simple symbols of good and evil, or ideal and villain, but fully realized human beings filled with inner contradictions. With this work, Cervantes not only created an immortal literary figure, but also opened a new path for storytelling and for exploring the depths of the human psyche in literature.

2. Summary of the Plot

Don Quixote tells the story of Alonso Quijano, a poor minor nobleman living in the region of La Mancha, who spends most of his time reading books of chivalry. His excessive immersion in these stories gradually erodes his ability to distinguish between fiction and reality. In Alonso Quijano’s mind, the world appears as a place full of injustice – one that desperately needs wandering knights to defend the weak, punish evil, and restore lost honor.

Driven by this belief, Alonso Quijano abandons his quiet life and reinvents himself as the knight-errant Don Quixote de la Mancha. He arms himself with a rusty suit of armor, names his scrawny horse Rocinante, and elevates an ordinary peasant woman into the noble lady Dulcinea, the ideal figure to whom he dedicates his service. From the very beginning, Don Quixote’s journey reveals a stark mismatch between the noble ideals of chivalry and the coarse, unyielding reality of everyday life.

In his early adventures, Don Quixote persistently interprets the world through the lens of chivalric romance. Dilapidated inns become grand castles, ordinary villagers turn into lords and ladies, and mundane events are transformed into epic dangers. Each of Don Quixote’s actions springs from goodwill and a sincere belief in justice, yet they often result in ridicule, violence, and humiliating defeat. His attack on the windmills, which he believes to be ferocious giants, has become a timeless symbol of the clash between illusion and reality.

Along the way, Don Quixote encounters and recruits Sancho Panza, a simple, pragmatic, and somewhat greedy peasant. Sancho follows Don Quixote not out of devotion to chivalric ideals, but in the hope of being rewarded with an island to govern. The contrast between Don Quixote and Sancho Panza forms the central dynamic of the entire narrative: one lives by faith and ideals, the other by practical experience and tangible interests. Yet the longer they travel together, the more they influence one another, blurring the boundary between idealism and realism.

The first part of the novel is largely comedic in tone, consisting of episodic adventures rich in symbolic meaning. Don Quixote is repeatedly defeated, deceived, or mocked, yet he remains steadfast in his identity as a knight. Beneath the laughter lies a quiet sorrow, as noble ideals are continually crushed by an indifferent and pragmatic society.

In the second part, the tone of the work becomes noticeably darker and more complex. Don Quixote is no longer merely an object of ridicule, but a figure deliberately manipulated by those who know his story from books. Many exploit his innocence by staging cruel pranks. Meanwhile, Sancho Panza – after being granted actual authority over an “island” – reveals unexpected growth, displaying fairness, kindness, and wisdom beyond expectations.

A series of defeats and shattered illusions ultimately exhaust Don Quixote both physically and spiritually. He returns home, abandons the identity of a knight, reclaims his original name Alonso Quijano, and awakens from the illusion that once sustained him. His death is calm and lucid, yet deeply moving, bringing to a close the journey of a man who lived fully by his ideals, even though those ideals had no place in the real world.

Through this seemingly simple plot, Don Quixote tells not only the story of a mad knight, but also reflects the spiritual journey of human beings as they confront a timeless question: should one live by what one believes is right, or compromise in order to survive in a world that has little tolerance for dreams?

3. Thematic and Artistic Value

The enduring value of Don Quixote lies not in its humorous episodes or its parody of chivalric romances, but in the way it poses a fundamental question: how should a person live when their ideals no longer align with the world around them? Don Quixote enters life with an absolute belief that justice, honor, and nobility can still redeem the world. Yet the reality he faces is rough and unforgiving, a place where such values have become obsolete or are dismissed as naïve.

At a deeper level, Don Quixote is not merely a “mad” individual, but a symbol of the tragedy faced by those who take their ideals seriously in a pragmatic society. Cervantes does not deny the absurdity of Don Quixote’s actions, but neither does he allow readers to mock him easily. As the story progresses, laughter gradually gives way to unease, as readers realize that Don Quixote fails not because his ideals are wrong, but because the world no longer permits such ideals to exist in a pure form.

One of the most distinctive thematic strengths of the novel lies in Cervantes’ construction of Don Quixote and Sancho Panza as opposing yet complementary forces. Don Quixote embodies the desire to transcend ordinary life, the belief that human beings can live more nobly than reality allows. Sancho Panza, by contrast, represents lived experience, practical wisdom, and basic human needs such as food, rest, and personal gain. Crucially, Cervantes does not absolutize either position. Idealism without realism becomes delusion; realism without idealism easily degenerates into mediocrity and moral emptiness. The constant tension between these two worldviews gives the novel its profound intellectual depth.

Artistically, Don Quixote marks a turning point in the history of the novel. Cervantes breaks away from traditional narrative forms by incorporating multiple narrative voices and layers of fiction intertwined with reality. He repeatedly plays with the boundary between “the story being told” and “the awareness of storytelling itself,” drawing readers into the narrative while simultaneously reminding them of its constructed nature.

Cervantes’ approach to character development was revolutionary for his time. Don Quixote is not a one -dimensional symbol, but a deeply contradictory human being: noble yet foolish, laughable yet admirable, fragile yet resolute. He evolves through experience and confrontation with life. Sancho Panza, likewise, is not merely a comic side character, but gradually emerges as a psychologically complex figure, capable of surprising moments of wisdom.

Another artistic strength of the novel lies in its narrative tone: humorous without being frivolous, satirical without being cruel. Cervantes uses laughter as a means of articulating uncomfortable truths about society and human nature. This laughter makes the novel accessible, while also softening the underlying tragedy, allowing Don Quixote to remain both approachable and profound.

Ultimately, the greatest value of Don Quixote lies in its timeless capacity for dialogue. The novel offers no definitive answer as to whether one should live idealistically or realistically. Instead, it leaves space for reflection. It is precisely this openness that has allowed Don Quixote to endure across centuries, serving as a mirror for the spiritual crises of humanity in every age – including our own.

4. Memorable Quotations

One of the reasons Don Quixote has endured for centuries is its abundance of seemingly simple sentences that contain remarkable philosophical depth. Beneath its humorous and satirical tone lie serious reflections on freedom, honor, idealism, and the human condition. Some of the words spoken by Don Quixote or Sancho Panza, when separated from their narrative context, stand on their own as profound observations about life.

The quotations below not only capture the spirit of the novel, but also help explain why Don Quixote, despite being a “failed” knight, has become a great humanistic symbol in world literature.

“Freedom, Sancho, is one of the most precious gifts that heaven has bestowed upon mankind; no treasure on earth can compare with it.”

In this statement, Don Quixote appears not as a delusional man, but as someone deeply aware of the fundamental value of human dignity – something many supposedly rational people readily sacrifice.

“A person’s honor lies within themselves, not in the judgment of others.”

In a world filled with prejudice and mockery, Don Quixote maintains his own moral standard, proving that he is far from insane in his understanding of human worth.

“He who loses the ability to dream also loses a part of his humanity.”

This line serves as a quiet defense of Don Quixote’s entire chivalric journey – ridiculed, yet never trivial.

“Not every defeated person is pitiable; only those who have never dared to step beyond their comfort deserve pity.”

Here, Cervantes overturns conventional measures of success, forcing readers to reconsider how they judge the value of a human life.

“People are often more afraid of being called mad than of living a meaningless life.”

This sentence causes laughter to falter, as it touches a very real fear of modern humanity: the fear of being different and excluded.

“Reality may knock us down, but only ideals give us a reason to rise again.”

This statement captures the central dialectic of the novel: realism and idealism are not mutually exclusive, but necessary to one another for a complete human existence.

“A knight may be defeated, but should never abandon what he believes to be right.”

For Don Quixote, failure does not negate the self, but becomes the cost of remaining faithful to one’s ideals.

“The laughter of others frightens me less than the silence of my own conscience.”

This line reveals Don Quixote as a character with a strong and consistent inner life, despite his isolation.

“Man does not live by bread alone, but by the things that give life meaning.”

Here, Don Quixote transcends his role as a comic figure to become a spokesperson for humanity’s spiritual longing.

Read slowly and within the broader framework of the novel, these quotations reveal that Don Quixote does not merely make us laugh at the naïveté of an old knight, but compels us to reflect seriously on how we are living – what we live for, and how many ideals we have abandoned on the path toward becoming “realistic.”

5. Conclusion

When Don Quixote comes to an end, what lingers is not the comic episodes or the image of an old knight charging at windmills, but a quiet sense of reflection about a man who lived fully by his ideals in a world that no longer had room for them. Don Quixote fails in every concrete adventure, yet he does not fail as a human being. He dares to believe, to dream, to act, and to pay the price for what he holds to be right.

At the same time, the novel does not glorify blindness or detachment from reality. Cervantes shows that ideals, when not anchored in awareness and lived experience, can turn into harmful illusions. Yet he also issues an equally stern warning: a life governed solely by pragmatic calculation, devoid of dreams and spiritual aspiration, ultimately becomes barren and meaningless.

For modern readers, Don Quixote is not a book that offers ready-made advice, but a mirror. Within each of us exists a Don Quixote – the part that longs to live nobly and meaningfully – and a Sancho Panza – the part that calculates, worries, and fears loss. The value of the novel lies in the fact that it does not force us to choose one over the other, but suggests that only through dialogue and balance between the two can a person live fully.

As a reader, Don Quixote is a book that makes us smile and then question ourselves. It urges us to reconsider the ideals we once held, the dreams we have neglected, and the compromises we have accepted in order to fit into the world. We may not – and perhaps should not – live like Don Quixote, but if we lose every trace of his “madness” in the way we see life, that may be the truly alarming loss.

For this reason, more than four centuries later, Don Quixote has not grown old. It remains not only a cornerstone of world literature, but also a persistent reminder that, in an increasingly pragmatic and skeptical world, preserving an ideal to believe in – something worth living for -may be one of the bravest acts a human being can undertake.