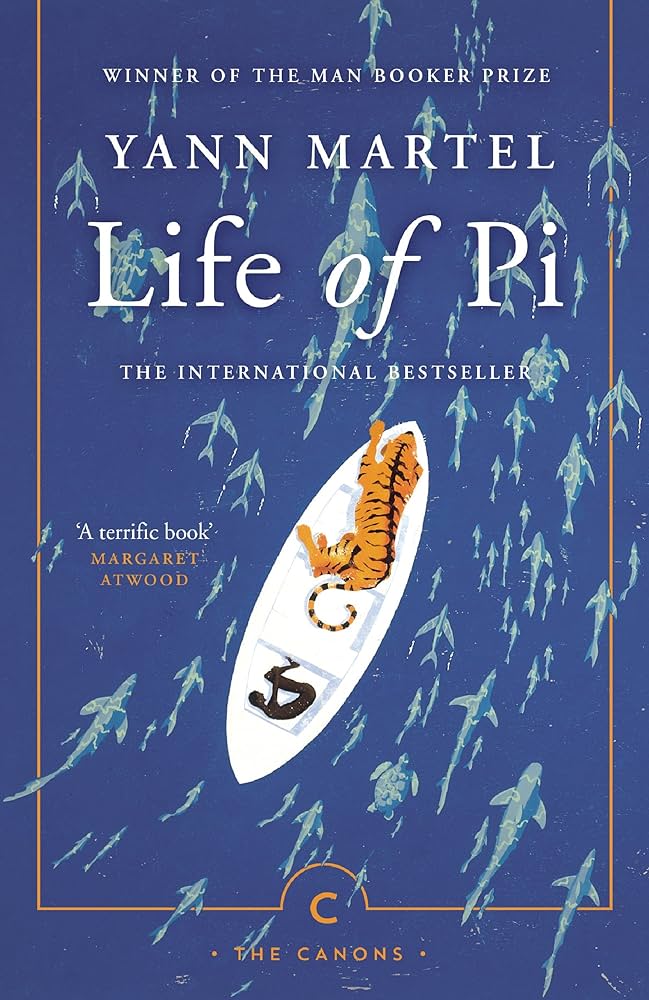

Life of Pi (original title: Life of Pi) is a renowned novel first published in 2001. From its release, the work quickly gained global attention thanks to its unique storyline, multi-layered narrative structure, and a philosophical depth rarely found in a popular novel.

The book won the Man Booker Prize in 2002, has been translated into dozens of languages, and has become one of the most widely taught and studied works of modern literature. The success of the novel was further extended through its film adaptation of the same name, bringing the story of Pi Patel closer to audiences worldwide.

Yann Martel is a Canadian writer, born in 1963 in Spain, and raised in a multicultural environment due to his father’s career in diplomacy. Living in many different countries and being exposed to diverse cultures, religions, and worldviews shaped Martel’s broad perspective on humanity and life.

Before Life of Pi, Yann Martel was not a particularly prominent name. However, after the resounding success of this novel, he came to be recognized as one of the outstanding contemporary writers, especially for his ability to combine literature, philosophy, and religion within a story that appears simple on the surface. Martel’s writing style is not flamboyant or ornate, but it always contains multiple layers of meaning, encouraging readers to reflect rather than merely consume the text passively.

2. Summary and analysis of the plot of Life of Pi

Pi’s childhood – Where faith and knowledge coexist

The protagonist of the story is Piscine Molitor Patel, commonly known as Pi. He is born and raised in India in a family that owns a zoo. From an early age, Pi is exposed to the animal world and learns that their instinct for survival is far from romantic; it is harsh and unforgiving.

What sets Pi apart is his deep fascination with religion. He simultaneously practices Hinduism, Christianity, and Islam, not because he ignores doctrinal differences, but because of his desire to understand God and the meaning of existence. This detail is crucial, as it lays the foundation for the entire ideological framework of the novel: faith is not meant to be proven, but to help people continue living.

The disaster at sea – The fragile boundary between life and death

Pi’s family decides to leave India for Canada, transporting many animals aboard a cargo ship. Disaster strikes when the ship unexpectedly sinks in the middle of the ocean. In the chaos, Pi loses his entire family and becomes the sole human survivor on a small lifeboat.

Pi is not alone on the boat. With him are an injured zebra, a hyena, an orangutan, and finally Richard Parker, a fierce Bengal tiger. One by one, the animals are killed according to the brutal laws of nature, leaving Pi stranded at sea for 227 days with only the tiger as his companion – or his enemy.

The struggle for survival – A battle of mind and instinct

The core of the novel lies in Pi’s long struggle to survive: learning to fish, collect rainwater, ration food, and most importantly, train the tiger to maintain a safe distance. The relationship between Pi and Richard Parker is one of the most profound symbols in the story.

Richard Parker is not merely a physical tiger. He represents primal survival instinct, the “animal” side that Pi is forced to acknowledge within himself. Because of the tiger’s presence, Pi cannot afford to give up. He must remain alert, disciplined, and focused on survival each day.

Here, Yann Martel does not shy away from cruelty: Pi must kill fish and turtles; he must witness death; he must face absolute loneliness. At the same time, the novel offers moments of wonder: the glowing sea at night, the carnivorous island, and the sense of being heard by God in the vastness of the ocean.

Two stories – One truth?

When Pi is finally rescued and brought back to land, investigators refuse to believe the story involving the tiger. Pi then tells another version, in which the animals are replaced by humans, and the events become far more brutal and stripped of fantasy.

In the end, Pi asks, “Which story do you prefer?” This question is the very soul of Life of Pi. What is the truth? Or do humans need a more beautiful story in order to accept reality?

3. Thematic value and artistic value of Life of Pi

In terms of thematic value, Life of Pi is foremost a work about human survival when pushed to the absolute limit. Through Pi Patel’s 227-day ordeal at sea, Yann Martel illustrates how, when all familiar structures – family, society, and rules – are stripped away, human beings are forced to confront their most basic survival instincts. However, the novel goes beyond a purely physical struggle against hunger and a hostile environment, delving into a deeper spiritual conflict shaped by loneliness, fear, despair, and the desire to believe in something greater than oneself. In this context, faith is portrayed not as a rigid religious doctrine, but as a spiritual anchor that keeps people from collapsing under the weight of suffering.

Another significant layer of meaning lies in the question of truth and how humans tell the truth. The two stories Pi offers at the end – one filled with animals and wonder, the other brutal and human – leave readers with a difficult question: which one is true? Or perhaps more importantly, which story allows people to continue living and come to terms with loss? Through this, Yann Martel suggests that humans do not live by objective truth alone, but by meaningful narratives and chosen beliefs that protect the soul.

In terms of artistic value, Life of Pi stands out for its multi-layered narrative structure, in which the boundary between reality and fiction is deliberately blurred. The calm, measured storytelling often resembles a factual account, yet beneath it lies a rich system of symbols. The vast ocean represents human isolation and uncertainty; Richard Parker is both a threat and a driving force for survival, symbolizing the instinctual side that humans must accept; the mysterious island appears as a tempting refuge that ultimately conceals death.

Yann Martel’s language is neither elaborate nor showy, yet it is rich in philosophical depth and emotional resonance. His descriptions of nature are both beautiful and indifferent, while Pi’s inner monologues are simultaneously innocent and profound. Together, these elements create a work capable of touching readers on multiple emotional and intellectual levels. This harmonious blend of adventure, philosophy, and refined storytelling is what makes Life of Pi a novel not only to be read once, but to be contemplated long afterward.

4. Memorable quotes from Life of Pi

One of the reasons Life of Pi is so widely loved lies in its seemingly simple sentences that conceal deep reflections on faith, fear, life, and the way humans face adversity. The following quotes function like spiritual fragments, contributing to the novel’s distinctive depth.

- “Life is a story. You can choose which story you believe.”

- “Fear is life’s only true opponent.”

- “When you lose everything, you understand what is truly necessary to live.”

- “Faith is a house with many open doors.”

- “Human beings have an extraordinary capacity to adapt when placed in extreme conditions.”

- “Despair is a very slow kind of death.”

- “To live, you must keep moving forward, even when you do not know where you are going.”

- “Hope is the last thing to leave a person.”

- “The silence of the ocean can sometimes be more frightening than any roar.”

- “You never know how strong you are until you have no other choice.”

- “Life always demands that we believe in something, even when reason cannot prove it.”

- “Life is not always noble, but it is always worth protecting.”

These sentences do not require specific context to move readers, because they reflect very real human experiences of loss, loneliness, and the desire to survive. This collection of quotes contributes greatly to making Life of Pi a book not only to read, but to remember and reflect upon.

5. Conclusion – A story to believe in, not to prove

Life of Pi does not attempt to persuade readers to believe in a specific religion, a supernatural miracle, or a single absolute truth. Instead, it chooses a quieter yet more humane path: granting each person the right to choose the story they wish to believe in, as long as that story is strong enough to help them keep living, stand firm in the face of loss, and not surrender to despair.

Through Pi Patel’s solitary struggle for survival, Yann Martel shows that in the harshest moments, humans need more than food and water – they need meaning to hold onto. When logic and reason fail before suffering, stories – whether shaped by faith or imagination – become spiritual lifebuoys that prevent people from sinking into hopelessness. From this perspective, Life of Pi does not emphasize determining what is right or wrong, true or false, but highlights the value of belief as a force that sustains existence.

For me, this is a book that should be read at least once in a lifetime – not to argue which story is true, nor to seek a final answer, but to pause and question oneself: when facing the “ocean” of one’s own life – inevitable losses, loneliness, and trials – what will we choose to believe in in order to move forward? Perhaps it is this very question, rather than any answer, that allows Life of Pi to remain so deeply embedded in the reader’s mind.