Within the flow of twentieth – century literature, Lord of the Flies is often cited as a representative work of critical reflection on civilization and human nature. Rather than choosing grand historical settings or direct social upheavals, William Golding situates human beings in a radically minimal space: a deserted island and a group of children without the presence of adults. It is precisely within this seemingly pure and harmless context that mechanisms of power, fear, and violence gradually emerge, develop, and ultimately spiral beyond control.

Lord of the Flies does not tell a story of growth or maturation in a positive sense; instead, it traces the gradual disintegration of order and morality once social constraints are removed. The novel raises a central and universal question: is civilization an inherent quality of humanity, or merely a fragile veneer sustained by rules and control? From this point, the work transcends the boundaries of fiction to become a text of profound intellectual significance, continually reread and analyzed across diverse cultural contexts.

1. Introduction to the Author and the Work

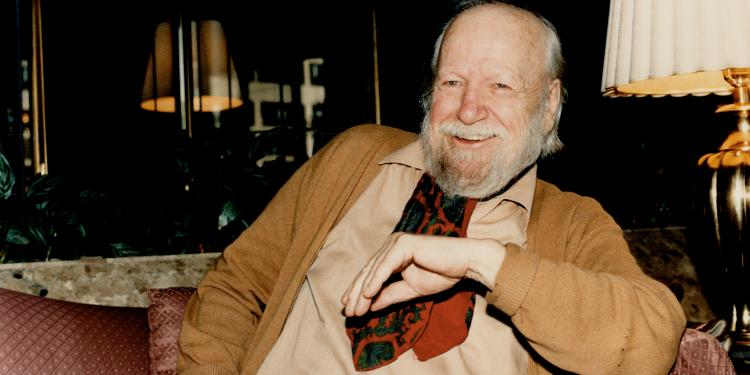

The author of Lord of the Flies is William Golding (1911–1993), an English novelist and one of the most important figures in world literature in the latter half of the twentieth century. Before establishing himself as a writer, Golding studied at Oxford University, initially focusing on natural sciences before shifting to English literature. This interdisciplinary academic background contributed significantly to a literary style that integrates philosophical, sociological, and psychological perspectives.

Golding’s personal experiences during World War II had a decisive influence on his worldview and artistic vision. While serving in the Royal Navy, he directly witnessed the brutality of war, the fragility of moral values, and the speed with which human beings could descend into violence under extreme circumstances. These experiences led him to fundamentally question the optimistic belief that human beings are inherently good and that human society naturally progresses toward moral improvement.

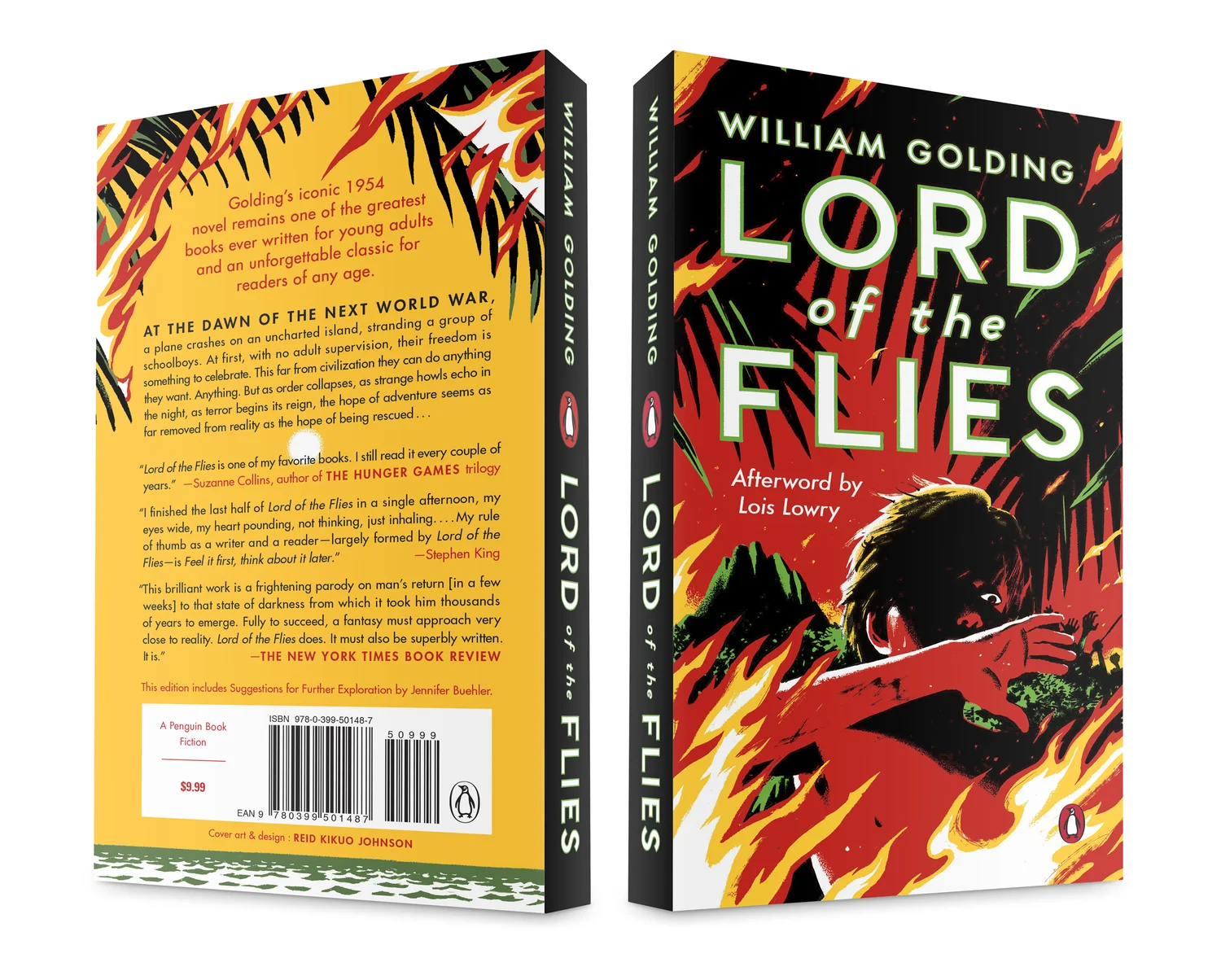

Lord of the Flies was first published in 1954 and was Golding’s debut novel. Prior to publication, the manuscript was rejected by numerous publishers due to its dark tone and its opposition to the prevailing trend of children’s adventure stories, which typically portrayed children as symbols of innocence and purity. Yet it was precisely this subversion that gave the novel its groundbreaking power. Golding refused to idealize childhood; instead, he portrayed children as complete human beings, capable of desire, power-seeking, and violence.

From its initial release, Lord of the Flies provoked intense debate because of its uncompromising approach to human nature. Over time, it came to be recognized as a symbolic novel and has frequently appeared on canonical lists of British and world literature. The book has been incorporated into educational curricula in many countries, not only in literature but also in disciplines such as philosophy, sociology, education, and political science.

With Lord of the Flies, William Golding laid the foundation for his entire literary career: a body of work rich in symbolism and consistently concerned with questions of evil, power, and the limits of human civilization. The novel is not only a milestone in Golding’s personal career but also a key text that reshaped how twentieth-century literature examines humanity and society.

2. Summary of the Plot

The story of Lord of the Flies begins with an airplane crash during wartime. A plane carrying a group of English boys is shot down, leaving the survivors stranded on a tropical deserted island, completely isolated from the adult world. With no guardians and no externally imposed rules, the island becomes a social experiment in which order must be constructed from nothing.

In the early days, the boys still adhere to behavioral patterns learned from civilized society. Ralph, a calm boy with leadership qualities, is elected chief through a democratic process, with a conch shell serving as a symbol of authority and the right to speak. Piggy, intellectually gifted but physically weak, functions as an advisor, representing reason, science, and organizational thinking. At the same time, Jack, the leader of the choirboys, gradually reveals his lust for power and inclination toward violence through his obsession with hunting.

Initially, the young community establishes goals aligned with survival and civilization: building shelters, maintaining a signal fire to attract rescue, and holding regular meetings to make collective decisions. However, impatience, conflicting priorities, and individual instincts soon expose deep fractures. While Ralph remains committed to rescue, Jack increasingly neglects the signal fire in favor of hunting and asserting dominance.

Alongside the struggle for power, fear spreads among the boys. Rumors of a mysterious “beast” on the island begin to dominate their imaginations, particularly among the younger children. Though the beast has no clear physical form, its psychological impact is immense, undermining reason and paving the way for violence. Jack quickly realizes that fear is a more effective instrument of control than any rule.

From this point onward, society on the island begins to disintegrate. Jack breaks away from Ralph’s group and forms his own tribe, where authority is enforced through violence, primitive rituals, and absolute obedience. Hunting ceases to be merely a means of obtaining food and becomes a collective ritual that unleashes instinct and erodes moral boundaries. The pig’s head mounted on a stake – the “Lord of the Flies” – emerges as a tangible embodiment of violence and collective fear.

The tragedy reaches its climax when Simon, a character endowed with moral intuition and deep insight, realizes that the “beast” does not exist externally but resides within human beings themselves. However, in a frenzy of collective hysteria, Simon is killed by the other boys. His death marks the complete collapse of rational moral judgment.

Soon afterward, Piggy – the final voice of reason and order – is brutally murdered during a confrontation. The conch shell, symbolizing law and dialogue, is shattered, signaling the definitive end of civilized society on the island. From this moment on, violence is no longer a means but the governing principle.

The story concludes with the sudden arrival of a naval officer who rescues the boys. Yet this ending offers no true catharsis. The image of the rescued children standing before an adult world engulfed in war creates a bitter contrast. Through this juxtaposition, Lord of the Flies extends its reflection: the island’s tragedy is not an anomaly of childhood, but a microcosm of human society at large.

3. Thematic and Artistic Value

The core value of Lord of the Flies lies in its challenge to one of the foundational assumptions of modern civilization: that human beings naturally progress morally. William Golding does not provide a direct answer, but the novel’s trajectory suggests a consistent argument – when external systems of control disappear, primitive instincts tend to surface rapidly and overpower so-called civilized values.

The island functions as a tightly structured social allegory. It is not merely a physical setting, but a miniature model of human society, containing power, law, belief, fear, violence, and submission. Crucially, these elements are not imposed from outside; they arise organically from human interaction under pressure.

Golding’s analysis of the relationship between fear and power is particularly incisive. The “beast” has no concrete existence, yet it exerts greater influence than any tangible threat. Fear becomes a tool of psychological manipulation, allowing violence to be justified and authoritarian power to be accepted. Evil, Golding suggests, requires neither grand ideology nor complex doctrine – only fear and collective silence.

Another distinctive thematic element is the novel’s demystification of childhood. Contrary to idealized notions of children as inherently innocent, Golding presents them as unmasked human beings, not yet constrained by social morality. Their descent is not portrayed as abnormal but as a revelation of latent human tendencies.

Artistically, Lord of the Flies is marked by a consistent and powerful system of symbols. The conch represents order, dialogue, and democracy; the signal fire symbolizes hope, reason, and connection to civilization; and the “Lord of the Flies” embodies violence, fear, and inherent evil. These symbols interact dynamically, reinforcing and negating one another as the story unfolds.

Golding’s characters function on both individual and symbolic levels. Ralph, Piggy, Jack, and Simon represent opposing principles – order and chaos, reason and instinct, morality and power. By forcing these principles into direct confrontation within a confined space, the novel achieves exceptional intellectual concentration.

Stylistically, Golding employs a restrained, almost detached narrative voice, avoiding overt moral commentary. This apparent neutrality intensifies the impact of violence, presenting it as the inevitable outcome of accumulated choices rather than emotional excess. Readers are compelled to confront ethical questions independently, without authorial guidance.

Ultimately, the value of Lord of the Flies lies not in dramatic twists, but in its philosophical depth and social reflection. Civilization, the novel suggests, is not a natural state but a fragile construct requiring constant maintenance. When awareness, responsibility, and self – restraint weaken, collapse can be swift and devastating.

4. Notable Quotations

One of the sources of Lord of the Flies’ intellectual depth lies in its concise yet highly generalizable statements. Golding avoids lengthy philosophical exposition, allowing characters to speak plainly, even coldly, while raising fundamental questions about morality, power, and human nature.

- “Maybe there is a beast… maybe it’s only us.”

This pivotal line shifts fear from the external world to the human psyche, asserting that evil is not an anomaly but a persistent potential. - “The rules are the only thing that makes us different from animals.”

Initially expressing faith in order, the statement later exposes how fragile the boundary between humanity and savagery truly is. - “The fire is the most important thing on the island.”

The fire symbolizes reason and hope; neglecting it signifies the abandonment of collective purpose. - “Fear can’t hurt you any more than a dream.”

Golding demonstrates how fear becomes destructive when ignored rather than rationally confronted. - “Power lies in fear.”

Authority in the novel is sustained not by reason but by psychological dominance. - “Hunting isn’t just about food anymore.”

Violence transforms into an end in itself, detached from survival needs. - “The conch exploded into a thousand white fragments.”

The destruction of the conch marks the death of dialogue and democracy. - “The darkness of man’s heart.”

This phrase encapsulates Golding’s central thesis: evil originates within. - “Civilization is a thin veneer.”

A succinct summary of the novel’s enduring message.

5. Conclusion

Lord of the Flies is not designed as entertainment but as an exploration of the deepest layers of human nature. Through a miniature social model on a deserted island, William Golding raises fundamental questions about evil, law, fear, power, and the fragility of civilization. These issues are not presented abstractly but embodied through psychological development and human action.

The novel refuses simplistic explanations. Golding neither blames circumstances alone nor idealizes humanity as innocent victims. Instead, he reveals the collapse of order as the result of intersecting forces: uncontrolled fear, the desire for power, the silence of reason, and collective irresponsibility.

Because its questions transcend historical and cultural contexts, Lord of the Flies remains perpetually relevant. What keeps humanity within civilization, and what drives it toward violence? When do laws hold meaning, and when do they become hollow symbols?

In its totality, Lord of the Flies secures its place as one of the most significant novels of the twentieth century. By refusing comforting resolutions and confronting readers with unsettling truths, it affirms that civilization is not a given – but a choice that must be continuously defended.