In the intellectual history of the twentieth century, few works emerging from extreme personal experience have managed to retain such universality and enduring academic value as Man’s Search for Meaning. The book was not written to recount the pain of war, nor merely to denounce the brutality of Nazi concentration camps, but to address a more fundamental question: the meaning of human existence when life is pushed to its ultimate limits.

What distinguishes Man’s Search for Meaning is its ability to connect lived experience with scientific thinking and existential philosophy. During his years of imprisonment, the author observed, analyzed, and distilled universal psychological patterns concerning motivation, endurance, and the human capacity to overcome adversity. As a result, the book transcends historical testimony to become a foundational intellectual work in modern psychology.

In contemporary society, where many individuals struggle with disorientation, crises of meaning, and spiritual emptiness, Man’s Search for Meaning remains strikingly relevant. The work poses an enduring question: what do human beings rely on to continue living when familiar sources of support collapse, and can meaning be discovered within suffering itself? From this question, the book develops a system of thought that has exerted profound and lasting influence.

1. Introduction to the Author and the Work

The author of Man’s Search for Meaning is Viktor Frankl (1905–1997), an Austrian neurologist, psychiatrist, and thinker, as well as the founder of Logotherapy – one of the three major pillars of twentieth-century depth psychology, alongside Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalysis and Alfred Adler’s individual psychology.

Viktor Frankl was born and raised in Vienna, one of Europe’s most important intellectual centers at the time. From his early years as a medical student, he showed a deep interest in issues related to psychological crises, depression, and the meaning of human life. Before the outbreak of World War II, Frankl conducted notable research and practical initiatives in suicide prevention among adolescents, demonstrating that his central concern was not merely mental illness, but the fundamental question of what motivates human existence.

A decisive turning point in Frankl’s life and thought came during World War II, when he and his family were arrested by the Nazis and deported to concentration camps. Over nearly three years, Frankl was imprisoned in several camps, including Auschwitz – an emblem of systematic dehumanization. Most of his family members, including his parents and his young wife, did not survive.

In circumstances where nearly all human rights were stripped away, Frankl did not exist merely as a prisoner; he also observed human behavior through the lens of a scientist. He studied the psychological responses of inmates as they confronted hunger, forced labor, the constant presence of death, and the absurdity of violence. From these observations, Frankl gradually formed a foundational insight: human beings can endure seemingly unbearable suffering if they can find a meaning to hold onto and strive toward.

After the war, Frankl returned to Vienna having lost almost everything – his family, the continuity of his career, and the manuscripts he had written before the war. Nevertheless, within a short period, he wrote Man’s Search for Meaning, drawing directly from his concentration camp experiences and the theoretical framework he had been developing for years. Initially, the book was not expected to achieve widespread recognition, yet it quickly captured the attention of both scholars and general readers due to its authenticity, concision, and rare intellectual depth.

In essence, Man’s Search for Meaning is not merely a war memoir but an intellectually pioneering text. Through this work, Frankl articulates the core principles of Logotherapy, asserting that meaning – rather than pleasure or power – is the primary driving force of human life. This perspective both builds upon and challenges prevailing psychological schools of thought, opening a new approach to understanding existential crises, depression, and loss of direction.

Since its publication, Man’s Search for Meaning has been translated into dozens of languages, continuously reprinted, and widely taught in psychology, philosophy, and social science curricula. Its influence extends beyond academic circles, reaching a broad readership through clear language, minimal technical jargon, and a consistent grounding of theory in lived experience.

It can be affirmed that understanding Viktor Frankl and the circumstances under which Man’s Search for Meaning was written is essential to grasping the spirit of the work. The book was not written from the perspective of a detached observer of life, but from that of someone who had reached the depths of suffering while retaining faith in the value of human existence.

2. Summary of the Core Content

Man’s Search for Meaning does not follow the structure of a conventional novel or memoir. Instead, it is a close integration of personal experience in concentration camps and psychological – philosophical analysis of human beings under extreme conditions. The book is divided into two major parts, with the first serving as a foundation by recounting lived experience while laying the groundwork for the Logotherapy framework presented later.

2.1. Life in the Concentration Camps from a Psychological Perspective

In the opening section, Viktor Frankl does not narrate his story as a purely personal account, but adopts an observational and generalized approach. He views the concentration camp as an “extreme laboratory,” where the familiar values of civilized life are destroyed, thereby revealing the core of human psychology.

Frankl describes the prisoners’ experiences through three main psychological stages.

The first stage is the initial shock.

Upon arrest and arrival at the camp, individuals experience profound mental disorientation. Fear is accompanied by a sense of unreality, as elements once taken for granted – name, profession, dignity – are erased in a short time. Alongside fear, however, exists a vague form of hope: many believe the ordeal is temporary, that release will come soon, or at least that conditions cannot worsen.

The second stage is adaptation and emotional numbness.

As violence, hunger, disease, and death become routine, prisoners develop psychological defense mechanisms to survive. Indifference, emotional blunting, and detachment emerge not because people lose their humanity, but because such responses are necessary to avoid being crushed by reality. Frankl observes that moral values are severely tested at this stage, as individuals face the dilemma between preserving their own survival and maintaining human dignity.

The third stage occurs after liberation.

Frankl analyzes a paradox: many prisoners do not experience the expected joy upon gaining freedom. After prolonged survival pressure, they lose the capacity to feel pleasure. Feelings of emptiness, disorientation, and even bitterness toward freedom emerge, demonstrating that psychological trauma does not automatically disappear when circumstances change.

Through these three stages, Frankl clarifies a crucial insight: harsh conditions do not homogenize people; rather, they reveal profound differences between individuals – especially in how they choose their attitude toward life.

2.2. Meaning as the Determining Factor of Survival

A central question running through the first part of the book is: what allows some people to survive while others collapse? Frankl rejects simplistic explanations based on physical strength or luck, emphasizing instead the decisive role of meaning.

According to Frankl, prisoners who possessed a clear spiritual goal – even a fragile one – were better able to endure suffering. For some, it was the hope of reuniting with family; for others, the responsibility to complete unfinished work; for Frankl himself, the desire to preserve and transmit ideas he believed held value for humanity.

More importantly, Frankl stresses that meaning does not always reside in distant future goals. It can be found in small daily choices: preserving dignity, helping another person, or refusing to allow circumstances to turn oneself into a cruel individual. These choices mark the fundamental difference between mere biological survival and meaningful existence.

2.3. From Lived Experience to the Foundations of Logotherapy

In the second part of the book, Frankl systematizes his observations into the theoretical framework of Logotherapy. This section is not detached from the camp experience but is built directly upon it.

Frankl argues that the deepest human motivation is not the pursuit of pleasure or power, but the pursuit of meaning. When meaning is lost, individuals fall into what he terms “existential vacuum,” a condition increasingly common in modern society.

He identifies three primary paths through which meaning can be discovered:

- Through work and creative contribution to the world.

- Through experience and love, particularly relationships with others.

- Through one’s attitude toward unavoidable suffering, when circumstances cannot be changed but one’s response can.

Central to Frankl’s thought is the affirmation of human spiritual freedom. Regardless of oppression, individuals retain the ability to choose their attitude. This capacity constitutes human dignity and opens the possibility of finding meaning even in suffering.

2.4. Overall Structure and Intellectual Progression

Viewed as a whole, Man’s Search for Meaning develops not along a timeline of events but along a trajectory of understanding. Concentration camp experience serves as the empirical foundation from which Frankl derives universal insights about humanity. The interplay between narrative and analysis allows the book to avoid two extremes: excessive emotionalism or excessive abstraction.

Through this structure, the work demonstrates that human beings can be reduced to the lowest level of existence while affirming that meaning does not depend entirely on circumstances, but on personal choice and responsibility.

3. Thematic and Artistic Value of the Work

Among works addressing war and human existence, Man’s Search for Meaning occupies a distinctive position because it does not center on historical events or tragic emotion, but on explaining how humans sustain spiritual existence under extreme suffering. Its value lies not merely in what is narrated, but in how experience is transformed into universal thought.

3.1. Thematic Value: Meaning as the Foundation of Human Existence

The core thematic value of Man’s Search for Meaning lies in establishing meaning as the central axis of human life. Frankl neither romanticizes suffering nor treats it as something to be avoided at all costs. Instead, he shows that suffering is an inescapable aspect of life, and that the meaning assigned to suffering determines the value of existence.

From the concentration camp reality, Frankl demonstrates that when all external factors – possessions, status, physical freedom – are stripped away, meaning becomes the final anchor preventing psychological collapse. This leads to a foundational claim: human life is not measured by comfort, but by meaning. This view directly challenges modern lifestyles centered on pleasure, convenience, and immediate gratification.

The work also clarifies the relationship between freedom and responsibility. Frankl argues that while individuals are not free to choose their circumstances, they are always free to choose their attitude toward them. Freedom, therefore, is inseparable from personal responsibility, a principle that elevates the book beyond memoir into a lasting philosophical statement.

3.2. Academic Contribution: Logotherapy and a New Psychological Perspective

Another significant contribution of Man’s Search for Meaning is its role in introducing Logotherapy. In a psychological landscape dominated by theories emphasizing instinct and drives, Frankl proposed a different approach: human beings as meaning-oriented entities.

Logotherapy does not deny biological or unconscious psychological factors but situates them within a broader framework where the spiritual dimension is central. Humans are not merely reactive beings; they possess the capacity for self-transcendence by orienting life toward meaning beyond the self.

This perspective is especially valuable in addressing depression, existential crises, and spiritual emptiness – issues increasingly prevalent in modern society. Rather than focusing solely on symptoms, Frankl redirects attention to the question: what is one living for? This shift provides both academic depth and practical relevance.

3.3. Humanistic Value: Affirming Human Dignity in Adversity

On a humanistic level, Man’s Search for Meaning powerfully affirms human dignity even under inhuman conditions. Frankl does not idealize camp inmates; he acknowledges moral degradation, cruelty, and selfishness. Yet he also observes individuals who maintained compassion, kindness, and moral responsibility.

The coexistence of degradation and transcendence reveals the openness of human nature. Rather than offering a simplistic moral judgment, the book confronts readers with a challenging question: who do we become when pushed to our limits? Its humanistic value lies in returning that answer to the individual.

3.4. Artistic Value: Restrained Tone and Coherent Intellectual Structure

Artistically, Man’s Search for Meaning is marked by a restrained, composed tone and a deliberate avoidance of melodrama. Frankl refrains from emotionally charged language, favoring an observational and analytical style. This restraint lends credibility and depth to the suffering described.

The structure of the work reflects logical thinking: experience precedes theory. This ordering allows readers to engage with philosophical ideas organically rather than feeling instructed. Abstract concepts are anchored in lived reality.

The integration of memoir, psychological analysis, and philosophical reflection enables the book to reach diverse audiences. This synthesis represents a major artistic achievement, balancing scholarly rigor with broad accessibility.

3.5. Enduring Relevance in the Modern Context

In today’s context, Man’s Search for Meaning remains highly relevant, particularly as individuals confront psychological pressure, identity crises, and imbalances between material and spiritual life. The book does not offer instant solutions but provides a durable framework for self-reflection.

Its lasting value lies in shifting the question from how to live to why one lives. This reframing allows the work to transcend its historical moment and maintain intellectual depth across generations.

4. Memorable Quotations

One reason Man’s Search for Meaning has endured lies in its concise yet profound statements. Frankl’s quotations are not superficial encouragements, but distilled insights forged through extreme experience, carrying significant philosophical weight.

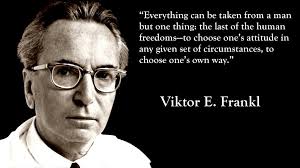

When addressing the ultimate boundary of human freedom, Frankl offers a foundational insight:

“Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms – to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances.”

From his observations in the camps, he summarizes the relationship between meaning and endurance:

“He who has a why to live can bear almost any how.”

Reflecting on love under inhuman conditions, Frankl states:

“Love is the ultimate and the highest goal to which man can aspire.”

In reference to modern society, he warns:

“The existential vacuum is the neurosis of our time.”

On suffering and control, he writes:

“When we are no longer able to change a situation, we are challenged to change ourselves.”

Regarding happiness, Frankl rejects direct pursuit:

“Happiness cannot be pursued; it must ensue as a by-product of a meaningful life.”

On responsibility, he asserts:

“Life ultimately means taking responsibility to find the right answer to its problems.”

Drawing from camp experience, he concludes:

“Life is never made unbearable by circumstances, but only by lack of meaning and purpose.”

Finally, reflecting on human nature, Frankl affirms:

“What is to give light must endure burning.”

Taken together, these quotations form a coherent system of thought centered on meaning, freedom, and responsibility, inviting sustained reflection rather than momentary inspiration.

5. Conclusion

Man’s Search for Meaning is neither a book of simple consolation nor a collection of easy prescriptions for overcoming suffering. Its core value lies in establishing a foundational principle: meaning is the spiritual pillar that determines how human beings exist and confront adversity. Through personal experience in concentration camps and rigorous psychological analysis, Viktor Frankl demonstrates that even in the harshest conditions, humans retain a minimal yet decisive freedom – the freedom to choose their attitude.

The work transcends the genre of war memoir to become an influential intellectual text in modern psychology and existential thought. Logotherapy, presented concisely within the book, not only introduces a new therapeutic approach but also reexamines the purpose of life in societies increasingly driven by efficiency and convenience. In this sense, Man’s Search for Meaning possesses both academic significance and practical relevance.

Notably, the book neither idealizes humanity nor denies suffering. Frankl acknowledges the human capacity for moral degradation while emphasizing that individual choice ultimately determines who one becomes. This balanced perspective allows the work to avoid both excessive pessimism and unrealistic optimism.

In the modern world, where many experience existential emptiness and value crises, Man’s Search for Meaning remains timely. It does not provide ready-made answers to happiness, but offers a stable framework for self-questioning and life orientation.

It can therefore be affirmed that Man’s Search for Meaning is among the rare works that combine academic rigor with lasting social influence. Its value lies not in answering how one should live, but in compelling each individual to confront the deeper question: what am I living for?