In the history of world literature written about war, especially the Second World War, there is no shortage of works that depict bombs, death, and collective suffering. However, very few books choose a different path: telling the story of war with gentleness, through stolen books, and through the perspective of Death – a witness to all loss who is not devoid of compassion. The Book Thief is such a work.

Rather than portraying war through grand scenes of destruction, The Book Thief focuses on small, intimate moments: a child learning to read, a man repainting words that have been blacked out, a family hiding a Jewish man in a cold basement. From these seemingly ordinary details, the novel raises a profound question: in an era when human dignity is systematically stripped away, can language still offer salvation?

Though born in the context of contemporary literature, The Book Thief carries enduring philosophical depth. It is not merely a historical novel, but a meditation on the power of words, human compassion, and memory in the face of a dehumanizing war machine.

1. Introduction to the Author and the Work

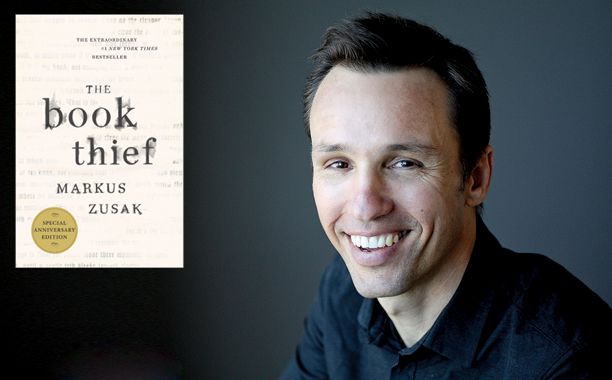

The Book Thief is the defining work that brought Markus Zusak beyond the boundaries of young adult literature and established him as one of the most widely read contemporary authors in the world. Markus Zusak was born in 1975 in Sydney, Australia, to a family of European origin: his father was German and his mother Austrian – both of whom directly experienced the Second World War. The war memories they shared with their son were not heroic tales, but stories filled with fear, loss, and the feeling of being mercilessly swept along by history. These lived experiences became the emotional and ideological foundation of The Book Thief.

Before achieving international success with this novel, Zusak had written several works for young readers, yet he was still regarded as a peripheral figure in mainstream literature. The Book Thief marked a major turning point in his career: it not only expanded his readership to adults, but also demonstrated his ability to address historical and philosophical issues through language that is simple yet weighty.

First published in 2005, The Book Thief quickly drew significant attention from critics and readers worldwide. The novel remained on bestseller lists for years, was translated into more than forty languages, and became one of the most widely taught literary works in secondary schools and universities across the United States, Europe, and Australia. Its success does not stem from epic portrayals of war, but from a radically different approach: viewing the Second World War through the lens of ordinary people living on the home front.

One of the most distinctive creative choices that sets The Book Thief apart is the selection of Death as the narrator. In this novel, Death is not a symbol of cruelty, but a weary witness, deeply haunted by human fate. This narrative perspective allows the author to maintain necessary distance from tragedy while simultaneously deepening the philosophical reflection on life, death, and humanity’s responsibility for its own actions.

In terms of genre, The Book Thief is often categorized as historical fiction or young adult literature. In reality, however, it transcends conventional classifications. The novel blends historical narrative, philosophical reflection, and mature literary sensibility, while addressing universal concerns: the power of language, collective memory, and the preservation of humanity under inhumane conditions.

It is precisely this convergence of the author’s personal inheritance, a brutal historical backdrop, and a distinctive narrative voice that has made The Book Thief a work of lasting relevance – one that continues to be read, analyzed, and discussed many years after its publication.

2. Summary of the Plot

The Book Thief is set in Germany during the darkest years of the Second World War – a period when war did not exist solely on battlefields, but infiltrated homes, streets, and individual lives. The story is narrated by Death, both an unwilling witness and the keeper of memories about a remarkable girl named Liesel Meminger.

Liesel’s journey begins with loss. On the train carrying her and her brother to their foster home, her brother dies from illness and starvation. During his cold burial, amid falling snow and the indifference of adults, Liesel accidentally picks up a book titled The Gravedigger’s Handbook. Though she cannot yet read, she keeps it as the last tangible memory of her brother – marking her first act of “book stealing,” driven more by instinct than intention.

Liesel is taken to Himmel Street in the town of Molching to live with her foster parents, Hans and Rosa Hubermann. Their small, impoverished home becomes the central setting of the story. Hans Hubermann, a kind-hearted house painter who loves music, patiently teaches Liesel to read using The Gravedigger’s Handbook. These nighttime lessons in the basement not only help Liesel overcome her recurring nightmares, but also form a father-daughter bond grounded in language and mutual understanding.

In contrast to Hans, Rosa Hubermann initially appears harsh, foul-mouthed, and abrasive. Yet beneath this rough exterior lies a resilient woman who shoulders the burden of family life amid poverty and war. Rosa represents the working-class German woman – reserved in expressing affection, but unwavering in her sacrifices.

Alongside family life, Liesel gradually integrates into the outside world, particularly through her friendship with Rudy Steiner, a blond-haired neighbor obsessed with African American athlete Jesse Owens and determined to become the fastest runner alive. Rudy embodies childhood innocence, mischief, and a yearning for recognition, while also falling victim to a society obsessed with racial ideology. His friendship with Liesel offers a rare light amid the darkness of war.

A major turning point occurs when the Hubermanns hide Max Vandenburg, a young Jewish man, in their basement. Max is the son of the man who once saved Hans’s life during the First World War, and it is this moral debt that compels Hans to risk everything to protect him. Max’s life in hiding – marked by illness, fear, and isolation – reflects the fate of millions of Jews hunted and erased from society.

The bond between Liesel and Max is built on shared language and deep empathy. Max writes stories for Liesel and paints over the pages of Mein Kampf, transforming a Nazi propaganda text into an act of resistance. Through Max, Liesel learns that words are not merely tools for storytelling, but can also serve as weapons against oppression.

On a broader social level, the novel vividly captures the suffocating atmosphere of wartime Germany: public book burnings, Jewish prisoners being marched through the streets, and increasingly frequent air raids. During one book burning, Liesel dares to steal a book that has not yet been fully consumed by flames – a symbolic act of quiet defiance against authoritarian power.

As bombings become routine, residents of Himmel Street shelter together in air-raid basements. There, Liesel reads aloud to calm their collective fear. In these moments, books cease to be private possessions and instead become communal lifelines in the face of death.

Tragedy reaches its climax when an unexpected bombing destroys Himmel Street. Hans, Rosa, and Rudy are all killed, leaving Liesel alive amid the rubble. The moment she finds Rudy’s body – the boy who never lived to receive her kiss – is among the most devastating scenes in the novel, marking the irrevocable end of her childhood.

Liesel survives not as a stroke of fortune, but as a bearer of memory. She carries with her a handwritten account of her life – The Book Thief – which Death retrieves and recounts to the reader. Through this act, the story becomes more than a personal memoir; it stands as testimony to ordinary people crushed by history, yet not entirely erased.

3. Thematic and Artistic Values of the Work

At its deepest level, The Book Thief is not a conventional war novel, but a work about how human beings endure within war. Markus Zusak does not focus on military campaigns or political conflict; instead, he turns his gaze toward the inner lives of small, powerless individuals – those who cannot choose history, but must live with its consequences.

War as a Force That Erodes Everyday Life

One of the novel’s most significant thematic achievements lies in its portrayal of war not through gunfire, but through the slow erosion of daily existence. War manifests as hunger, persistent fear, nightly bombings, and prolonged insecurity. It seeps into meals, sleep, and family relationships.

Through Himmel Street – a poor, unremarkable neighborhood – the novel demonstrates that war recognizes no historical center. Ordinary people with no power still pay the price with their lives, childhoods, and memories. This universality gives The Book Thief enduring relevance: any society drawn into war can generate similar tragedies.

Language: Instrument of Oppression and Means of Salvation

The novel’s core ideological strength lies in its treatment of language as the central site of conflict. In The Book Thief, words exist in stark duality. On one hand, language is manipulated by fascist power – slogans, speeches, and propaganda books mobilize hatred and legitimize violence. The Nazi regime does not rely solely on weapons, but on words to enforce obedience.

On the other hand, language becomes a means of protection against dehumanization. Liesel’s journey into literacy, her acts of book stealing, and her reading aloud in bomb shelters reveal language’s ability to create an alternative mental space – one where people can reclaim humanity and community.

Most powerfully, Max Vandenburg’s act of rewriting his story over the pages of Mein Kampf carries profound symbolic weight. A book that once embodied destructive ideology is transformed into a vessel of resistance. The novel thus asserts that words are not innocent, but humans retain the right to reclaim them.

Memory and Storytelling as Moral Acts

The Book Thief also raises questions about collective memory and ethical responsibility in recounting the past. Death’s role as narrator is not merely a stylistic device, but a philosophical stance. Death does not judge or justify; it remembers and tells. Storytelling becomes a moral obligation – to prevent ordinary lives from being forgotten.

The book Liesel writes – The Book Thief itself – serves as a repository of memory. It affirms that history is not shaped solely by grand events, but by individual stories and personal loss. Recording memory thus becomes an act of resistance against erasure.

Artistic Values: Narrative Voice, Structure, and Language

Artistically, the novel stands out for its choice of Death as narrator – a bold yet effective decision. This Death is neither cold nor terrifying, but weary, haunted, and reflective. The narrative voice creates sufficient distance to prevent emotional overload, while still conveying profound loss.

The nonlinear structure, including early revelations of certain deaths, shifts the reader’s focus from outcome to experience. Zusak compels readers to confront the idea that in war, what matters is not when death arrives, but how people live before it does.

The language is restrained, simple, and richly evocative. Many passages carry poetic qualities, employing metaphor and personification to render heavy themes accessible without diminishing their depth.

4. Memorable Quotations

One reason The Book Thief endures in readers’ memories is its contemplative, quietly haunting prose. The novel’s quotations do not merely sound beautiful; they encapsulate its core reflections on war, humanity, memory, and the power of words.

From the very beginning, Death’s voice subverts conventional expectations of mortality:

“I can be amiable. Agreeable. Affable. And that’s only the A’s.”

This perspective shifts attention from death itself to the burden carried by the living.

As Liesel enters the world of words, the novel reveals the complexity of language:

“I have hated the words and I have loved them, and I hope I have made them right.”

Language is both weapon and refuge – never pure, yet indispensable.

At moments of reflection, Death appears less as an executioner than as a witness:

“Even death has a heart.”

The cruelty of the world lies not in death, but in human behavior.

When books become lifelines, the novel affirms literature’s spiritual necessity:

“Sometimes a person is lucky enough to live by their words.”

Here, survival is framed as psychological endurance.

On humanity’s destructive tendencies, Death observes:

“The problem with humans is that they don’t know when to stop.”

This indictment extends beyond war to power, greed, and collective blindness.

One of the novel’s most striking images captures its essence:

“The girl stood in the rubble and collected the words.”

Amid destruction, language becomes an act of preservation.

The danger of silence is also laid bare:

“Silence is so damn loud.”

Injustice thrives where voices remain absent.

Reflecting on children in wartime, the novel offers a painful truth:

“War doesn’t just kill people. It steals childhoods.”

Emotional loss outweighs physical harm.

Ultimately, the novel distills itself into a meditation on memory:

“Stories are meant to be told so that people don’t forget.”

This is the very purpose of The Book Thief.

5. Conclusion

The Book Thief is not a traditional war novel, but a work about what remains of humanity after war. Through the story of Liesel Meminger and the ordinary residents of Himmel Street, Markus Zusak shifts focus from grand historical narratives to individual lives – from statistics to memory, emotion, and fragile existence in the face of violence.

The novel’s lasting power lies in its placement of language at the center of conflict. Books are burned, censored, and controlled, yet they also preserve humanity, memory, and empathy. In a world where brutality is justified through discourse, reading, writing, and storytelling become quiet but persistent acts of resistance.

On a personal level, The Book Thief does not overwhelm with dramatic climax, but leaves a lingering ache long after the final page. Its pain does not erupt; it settles – within basement lessons, hidden books, and a kiss never returned. This restraint makes the tragedy more authentic and enduring.

On a broader scale, the novel asks a universal question: what can humanity preserve when all social values collapse? Its answer lies not in victory or defeat, but in remembering, telling, and refusing to turn away from others’ suffering. Death’s role as narrator reinforces the idea that the greatest danger is not dying, but being forgotten.

In closing, The Book Thief is a deeply humanistic work, resonating with lovers of literature, history, and those seeking meaning in reading and writing during uncertain times. It does not demand tears – but it demands reflection: on war, on language, and on humanity’s responsibility to collective memory.