There are books that are not merely read, but entered. There are fictional worlds that do not exist on any map, yet feel so vividly alive that readers can hear the wind passing through ancient forests, feel the chill of snow-covered mountains, and carry with them the quiet melancholy of ages long past. The Lord of the Rings is such a world – a place where the boundary between literature and myth seems to dissolve.

Far from being a simple work of fantasy, The Lord of the Rings unfolds as a monumental epic about the human condition: about power and temptation, about a fragile yet enduring light of goodness amid seemingly endless darkness. The work draws readers away from familiar reality and into Middle-earth – a realm shaped by extraordinary imagination, profound intellectual depth, and a rare humanistic spirit.

What makes The Lord of the Rings truly distinctive does not lie in its grand battles or dazzling magic, but in the way the story places small, seemingly insignificant beings before choices of profound consequence. Here, the fate of the world is not decided by gods or invincible heroes, but by ordinary individuals – and Hobbits – who carry fear and weakness within them, yet still choose to move forward out of responsibility and love.

Reading The Lord of the Rings is not merely following a quest to destroy evil; it is witnessing an inner journey within each character – a journey of self-confrontation. Power is portrayed not as glory, but as burden; victory does not arrive in triumphant splendor, but is steeped in loss and sacrifice. It is this depth that allows the work to transcend the boundaries of entertainment literature and become a cultural symbol, a spiritual reference point for generations of readers worldwide.

1. Introduction to the Author and the Work

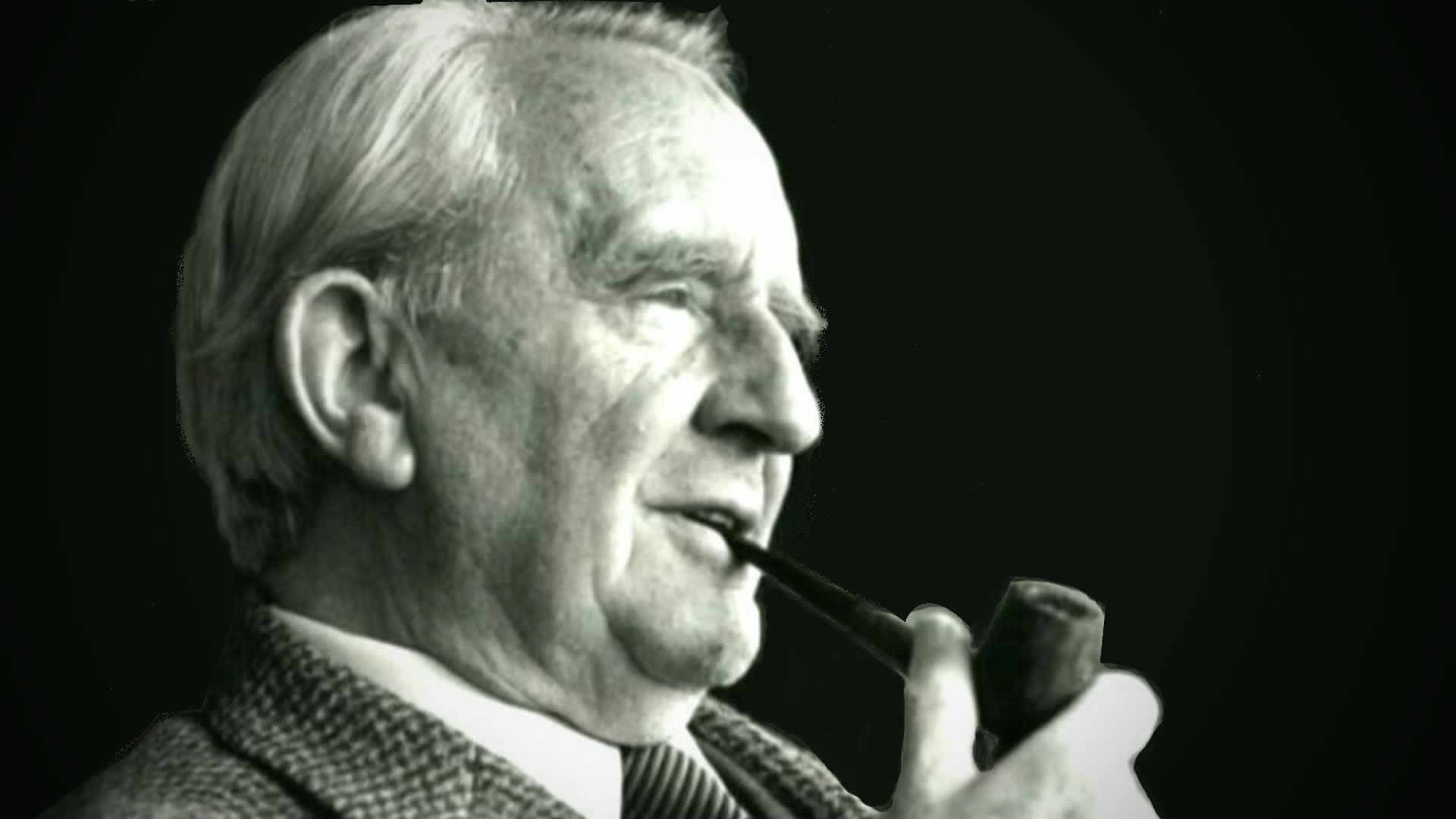

Behind the vast world of Middle-earth, behind pages dense with history, mythology, and ancient languages, stands the imprint of a rare intellect in world literature: J. R. R. Tolkien. He was not only a novelist, but first and foremost a distinguished scholar, an exceptional philologist, and a man who devoted his life to listening to the echoes of the past.

Born in 1892 in England, Tolkien came of age in a Western world shaken by war and a crisis of belief. His direct experience of the First World War, and his witnessing of the destruction and loss of an entire generation, left a deep mark on his thinking and worldview. Yet rather than writing direct indictments of war, Tolkien chose another path: the creation of a fictional world in which enduring questions about power, evil, sacrifice, and hope are explored with persistence and depth.

With a solid academic foundation at the University of Oxford, Tolkien possessed profound knowledge of ancient languages such as Anglo-Saxon, Norse, and Latin. From this foundation, Middle-earth emerged not merely as an invented setting, but as a world “with memory” – with millennia of history, diverse races, and distinct cultures, languages, and traditions. This explains why The Lord of the Rings does not feel like a fabricated story, but rather like a chronicle recorded from a vanished age.

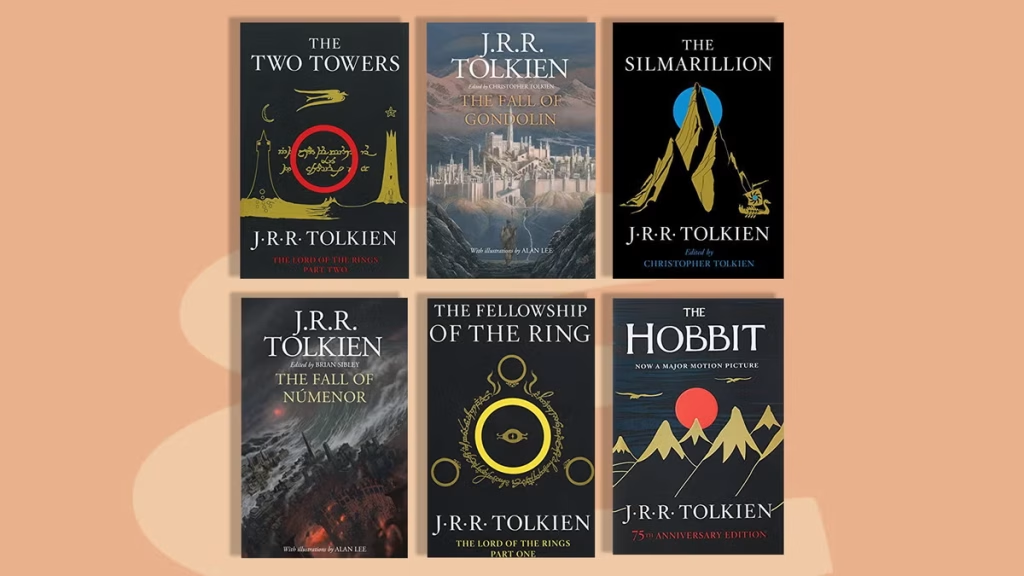

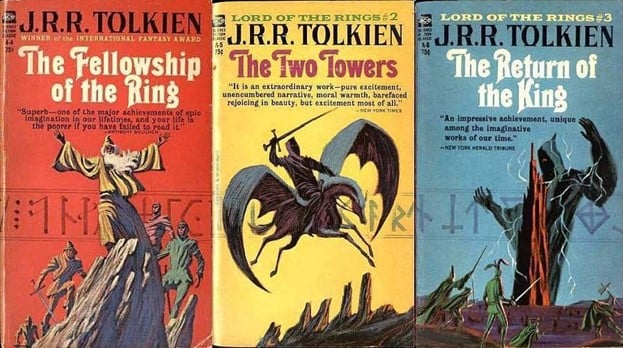

Conceived over many decades and first published between 1954 and 1955, The Lord of the Rings consists of three closely connected volumes. Although initially written as a sequel to The Hobbit, the work quickly surpassed the scope of a simple adventure tale to become a modern epic, in which every detail – from songs and place names to ancient legends – contributes to a unified depth.

Upon its release, The Lord of the Rings sparked considerable debate. Some critics considered it too long, too slow, and too “old-fashioned” for contemporary tastes. Time, however, has affirmed its value. Not only did it become a foundation for modern fantasy literature, but it also exerted profound influence on film, music, games, and global popular culture.

More importantly, The Lord of the Rings helped establish a new standard for fantasy: the genre is not merely an escape from reality, but a means of reflecting upon humanity itself. At the center of that standard stands J. R. R. Tolkien – a quiet storyteller who used myth to articulate some of the most enduring truths of human existence.

2. Summary of the Plot

The story of The Lord of the Rings begins in the peaceful setting of the Shire – a green and fertile land where the small Hobbits live simple lives, devoted to gardens, meals, and modest pleasures. In this seemingly isolated place, far removed from the turmoil of the wider world, an ancient threat quietly returns, carrying a darkness capable of engulfing all of Middle – earth.

The Ring that Bilbo Baggins brought back from his adventure in The Hobbit initially appears to be little more than a curious keepsake. Over time, however, the wizard Gandalf uncovers a terrifying truth: it is the One Ring, the embodiment of the power of Sauron, the Dark Lord who once nearly dominated Middle-earth. The Ring does not merely grant power; it corrupts the will, awakens ambition, and gradually destroys the soul of its bearer.

As Sauron rises again and begins searching for the Ring to complete his absolute dominion, Frodo Baggins – Bilbo’s nephew – is forced to leave the Shire. Not driven by heroic ambition, but by an inescapable sense of duty, Frodo carries a burden far beyond the strength of a Hobbit: to take the Ring to Mount Doom in Mordor, the only place where it can be destroyed.

On the journey out of the Shire, Frodo and his companions repeatedly face danger. The Black Riders, the Nazgûl, relentlessly pursue them, darkness spreads, and the world beyond the Shire reveals itself to be far harsher and more unstable than Frodo had ever known. This flight is not only a physical journey, but an awakening: Frodo begins to understand that Middle-earth stands on the brink of a decisive war.

At Rivendell, a council of the free peoples is convened. There, the full truth about the Ring is revealed, and a momentous decision is made: the Ring cannot be used, nor can it be hidden – it must be destroyed. The Fellowship of the Ring is formed, comprising representatives of Hobbits, Men, Elves, Dwarves, and a wizard – not as an invincible army, but as a fragile symbol of unity against the darkness.

From the outset, however, the Fellowship’s journey exposes this fragility. Differences in purpose, nature, and susceptibility to temptation continuously test the group. The Ring increasingly reveals its corrupting influence, causing even the strongest to waver. The fall of Boromir – a brave warrior unable to overcome his desire to use the Ring to save his people – becomes a painful warning of the cost of power.

After this turning point, the Fellowship breaks apart. Frodo chooses to continue the most dangerous path alone, accompanied only by the loyal Samwise Gamgee. Meanwhile, Aragorn, Legolas, and Gimli are drawn into great battles that determine the fate of human kingdoms. The Battle of Helm’s Deep, the rise of Isengard, and the schemes of Saruman reveal that darkness comes not only from Mordor, but also from betrayal and moral collapse within the ranks of the free peoples.

Parallel to these epic conflicts is the increasingly harrowing journey of Frodo and Sam. As they press deeper into Mordor, they face not only hostile terrain and lurking enemies, but also intense psychological erosion. The Ring grows heavier – not physically, but spiritually. Frodo becomes increasingly exhausted, suspicious, and even distant from Sam, demonstrating that even the purest souls are not immune to the corrupting force of power.

The climax occurs at Mount Doom. Having reached the limits of strength and faith, Frodo faces the decisive moment. Here, Tolkien makes a bold choice: the bearer of the quest does not prevail through absolute willpower. Frodo fails at the final instant. Yet Sauron’s downfall arises from another source – the chain of consequences born of greed, error, and earlier choices. Evil ultimately destroys itself.

After the victory, Middle – earth is liberated, but the triumph does not resemble a conventional happy ending. The world enters a new age, one in which magic fades, ancient races withdraw, and those who bore the greatest burdens cannot fully return to their former lives. Frodo comes back to the Shire carrying wounds of the spirit that will never entirely heal.

The Lord of the Rings concludes not with the splendor of power, but with a quiet, somber sense of maturity. The journey is complete, evil is defeated, yet the price is the loss of youth, innocence, and a world that can never be restored.

3. Thematic and Artistic Value

What allows The Lord of the Rings to transcend the framework of a conventional fantasy novel is the depth of thought it pursues. Beneath the surface of magic, mythical creatures, and epic battles lies a sustained meditation on power, morality, and human destiny. Tolkien does not tell a story in which evil is defeated by greater force; instead, he poses a more fundamental question: what happens when absolute power is placed in human hands?

The Ring – the core of the entire narrative – is not simply a symbol of evil, but a test for every character. It does not compel wrongdoing, but awakens the deepest desires: the urge to control, the fear of loss, the illusion that power can be wielded for noble ends. Consequently, the tragedy of The Lord of the Rings does not arise from purely evil figures, but from good individuals who lack sufficient humility before power. Tolkien’s warning is enduring: evil does not exist solely outside humanity, but emerges from its inner shadows.

Alongside the theme of power is a profound humanistic emphasis on sacrifice. Tolkien does not construct invincible heroes in the classical sense. Frodo is fragile, fearful, and often close to surrender. Sam possesses neither exceptional intellect nor extraordinary strength. Yet it is precisely this ordinariness that gives the narrative its emotional depth. The victory of good does not result from perfection, but from the ability to continue when hope appears exhausted. This deeply human perspective allows the mythic narrative to resonate with modern readers.

Another notable value of the work is its sober view of war. Although written in epic form, Tolkien does not romanticize violence. Every victory entails loss; every battle leaves scars that cannot be erased. When the war ends, the world does not revert to its former state, but transitions into a new age – one in which magic fades and old values give way to a new order. This conclusion reflects Tolkien’s understanding of war as a historical inevitability that leaves lasting psychological and cultural consequences.

Artistically, The Lord of the Rings represents a rare achievement in world-building. Middle – earth is not merely a setting, but a “living entity” with a history spanning thousands of years, distinct races, and inherited traditions. Tolkien never reveals everything, yet consistently conveys the sense that behind every place name and song lies a vast reservoir of untold memory. This implicit depth lends extraordinary credibility to his fictional world.

Language itself is another major artistic accomplishment. Tolkien’s prose is classical and measured, often bearing the cadence of epic poetry. He does not pursue immediate dramatic impact, but allows the narrative to unfold gradually, enabling meaning and emotion to settle. Descriptions of nature and interwoven songs do more than embellish the text; they shape the spirit of Middle-earth – a world in which beauty and loss coexist.

The greatest value of The Lord of the Rings lies in its universality. Though written within a specific historical context, the work is not confined by its era. Its questions about power, responsibility, choice, and the cost of victory retain their relevance in the contemporary world. For this reason, the novel transcends the boundaries of entertainment fiction and stands as an intellectual milestone in modern literary history.

4. Notable Quotations

A great work is remembered not only for its plot or its magnificent world, but also for sentences that remain in the reader’s mind long after the final page. The Lord of the Rings possesses a distinctive body of quotations: never ostentatiously philosophical or didactic, yet quietly planting enduring reflections on life, choice, and the human condition.

Behind arduous journeys lie words that appear simple, but gain universal significance within their narrative context, extending beyond the realm of Middle-earth.

From the outset, Tolkien subtly challenges conventional ideas of destiny and life’s path with a well-known line that serves as a reminder of the value of individual journeys:

“Not all those who wander are lost.”

In a world where power is often associated with strength and status, Tolkien places hope in the smallest figures. This line speaks not only of Hobbits, but of the historical role of ordinary individuals:

“Even the smallest person can change the course of the future.”

Amid relentless upheaval, the narrative repeatedly pauses to reflect on time – something humans cannot choose, yet can decide how to use:

“All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given to us.”

When darkness seems overwhelming and hope fragile, Tolkien refuses absolute despair, allowing his characters to affirm the persistence of light:

“There is some good in this world, and it’s worth fighting for.”

One of the work’s most profound human insights lies in its understanding of victory. Triumph does not arise from total destruction, but from refusing to become evil oneself:

“Evil cannot be destroyed by its own tools.”

Friendship and loyalty, especially embodied in Sam, are portrayed as quiet yet enduring forces that enable individuals to exceed perceived limits:

“I can’t carry it for you, but I can carry you.”

Conversely, Tolkien directly addresses the cost of power and temptation. The wounds they inflict are not always visible on the body:

“There are wounds that time cannot heal, for they are etched into memory.”

When the war ends, the narrative does not close with unrestrained celebration, but with a subdued awareness of loss – a mature, deeply human sorrow:

“We have changed. Not everything can return to the way it was.”

Finally, running throughout the entire work is a quiet conviction that simple virtues can withstand even the greatest darkness:

“Simple kindness, when held to the end, can be stronger than any power.”

Detached from the context of Middle-earth, these quotations retain their relevance as reflections on real life. This is why The Lord of the Rings is not merely read once, but continually returned to – each time revealing new meaning in words that once seemed familiar.

5. Conclusion

The Lord of the Rings is among the rare works that achieve both epic scope and enduring philosophical depth. Through the meticulously constructed world of Middle – earth, the novel does more than recount a quest to defeat evil; it confronts fundamental human concerns: the nature of power, the limits of human will, the meaning of sacrifice, and individual responsibility in the face of collective destiny.

The lasting value of the work lies in its humane and measured perspective. Evil in The Lord of the Rings is not defeated through overwhelming force, but through the refusal to wield corrupting power. Central characters are not unrealistically idealized; they stumble, hesitate, and carry lasting wounds after victory. This perspective allows the novel to move beyond traditional heroic models and articulate a profound understanding of the cost of history and war.

Artistically, The Lord of the Rings establishes a new benchmark for modern fantasy literature. Its synthesis of epic structure, mythological depth, and a coherent linguistic and historical system creates a fictional world of exceptional credibility. The work’s influence extends beyond literature into film, music, and global popular culture.

It can be affirmed that The Lord of the Rings is not merely a classic fantasy novel, but a literary achievement of enduring intellectual and artistic significance. The work continues to be studied, reread, and reinterpreted across generations, standing as testimony to literature’s capacity to illuminate the most fundamental and lasting questions of the human condition.