Within the broader landscape of contemporary Japanese manga, where comics are no longer merely a form of pure entertainment but increasingly function as a space for reflection on humanity and society, Tokyo Ghoul emerges as a work of pivotal significance. Released at a time when traditional heroic archetypes were gradually revealing their limitations, Sui Ishida’s manga chose a more daring path: placing human beings in a state of existential crisis, where the boundary between humanity and inhumanity becomes profoundly blurred.

Rather than constructing its world through a simplistic opposition between good and evil, Tokyo Ghoul portrays a familiar modern Tokyo enveloped in layers of latent conflict. Humans live in constant fear of creatures known as ghouls, while ghouls exist as social outcasts, forced to resort to violence in order to survive. This parallel coexistence forms the foundation of a narrative that is not merely about monsters, but more fundamentally about how society defines, excludes, and legitimizes violence against the “other.”

What distinguishes Tokyo Ghoul is not its intense combat scenes or shock-driven horror elements, but the psychological and philosophical depth embedded throughout the work. Through the journey of its protagonist, Kaneki Ken, the series raises philosophical questions: what does it mean to be human, can one’s nature be altered by circumstance, and does life hold equal value when society imposes unequal conditions of existence? This approach allows Tokyo Ghoul to transcend the framework of conventional entertainment manga and become a work rich in critical reflection, leaving a lasting impression on both readers and critics.

1. Introduction to the Author and the Work

Author: Sui Ishida

Sui Ishida (石田スイ), born in 1986 in Fukuoka Prefecture, is a representative figure of a generation of Japanese mangaka that matured during a period when manga began shifting toward greater psychological and ideological depth. Lacking formal training in traditional art institutions, Ishida entered the manga industry through self-study, drawing significant influence from existential literature, psychological cinema, and contemporary artistic movements. These influences contributed to a highly personal creative style, distinct from conventional commercial manga storytelling.

Prior to achieving widespread recognition with Tokyo Ghoul, Ishida produced several short works and one-shots, most notably The Old Man of the Mountain, which already demonstrated his inclination toward portraying isolated characters, complex inner lives, and dark, oppressive settings. Rather than focusing on idealized heroes or linear narratives of victory, Ishida concentrates on psychological fragmentation, disorientation, and the modern human desire for recognition and acceptance.

During the creation of Tokyo Ghoul, Ishida repeatedly described the work as an experimental project – one in which he could merge horror and action with philosophical concerns such as ontology, free will, and the distinction between the “human” and the “non-human.” This orientation has led to his recognition as an independent-minded creator who significantly expanded the thematic and expressive scope of contemporary Japanese manga.

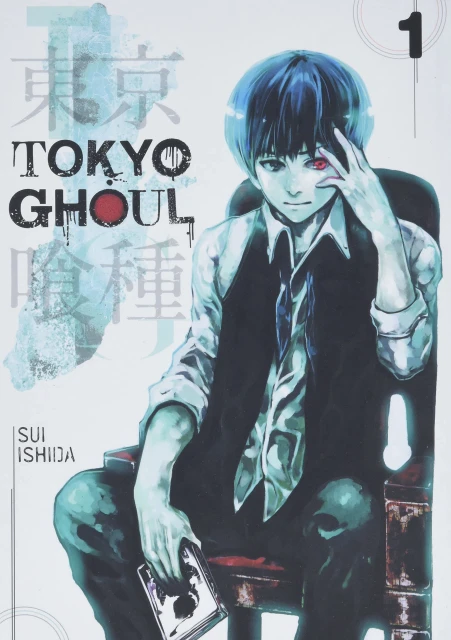

The Work: Tokyo Ghoul

Tokyo Ghoul was first published in 2011 in Weekly Young Jump, a magazine by Shueisha aimed primarily at mature readers. The original series ran until 2014, comprising 14 volumes, before continuing with the sequel Tokyo Ghoul:re (2014–2018), bringing the total number of volumes to 30. This division into two parts was not merely a commercial decision, but also reflected a marked shift in narrative structure and psychological depth.

From its earliest chapters, Tokyo Ghoul attracted attention through its construction of a world that is both familiar and alien: a modern Tokyo in which ghouls – beings who appear human but must consume human flesh to survive – live covertly among ordinary people. Rather than adopting a mythological or purely fantastical approach, the series situates horror within a highly realistic urban environment, intensifying the sense of unease and alienation embedded in everyday life.

In terms of genre, Tokyo Ghoul is classified as horror, action, and psychological manga, yet its core value lies in its transcendence of genre boundaries. The narrative extends beyond a simple conflict between humans and ghouls to depict a complex system of power, institutionalized violence, and social mechanisms that legitimize exclusion. Through organizations such as the CCG and various ghoul factions, Tokyo Ghoul exposes processes of dehumanization on both sides, raising ethical questions that resist simple resolution.

The success of Tokyo Ghoul is evident not only in its impressive sales and global readership, but also in its enduring cultural impact. Adapted into anime, novels, video games, and other media forms, the work has become a frequent subject of discussion within academic and critical manga communities. For these reasons, Tokyo Ghoul is widely regarded as a representative work marking the “maturation” of Japanese manga during the 2010s.

2. Summary of the Plot

Tokyo Ghoul opens in the familiar setting of a modern Tokyo, where urban life appears to proceed normally beneath neon lights and crowded streets. Beneath this orderly surface, however, exists the hidden presence of ghouls – beings who resemble humans but must feed on human flesh to survive. Their existence plunges society into a state of latent fear, managed by the CCG, an organization tasked with investigating and exterminating ghoul threats.

At the center of the story is Kaneki Ken, a quiet, introverted university student whose inner life revolves around books and private reflection. His life takes a dramatic turn following a fateful encounter with Kamishiro Rize, a dangerous ghoul disguised as an ordinary young woman. After a brutal attack and a near-fatal accident, Kaneki survives only through an organ transplant using Rize’s organs, transforming him into a half-ghoul – an existence rejected by both humans and ghouls alike.

From this point onward, Tokyo Ghoul follows Kaneki’s struggle to adapt to his new body and instincts. He can no longer consume human food and must confront an ever-present ghoul hunger that threatens to shatter the moral principles he once upheld. The café Anteiku becomes a temporary refuge, introducing him to ghouls who attempt to coexist quietly with humans, thereby offering an alternative perspective on a community widely regarded as monstrous.

Parallel to Kaneki’s survival journey is the escalating conflict between ghouls and the CCG. Increasingly violent investigations and purges not only intensify bloodshed but also expose internal contradictions within each faction. CCG investigators, despite their mission to protect humanity, are drawn into cycles of violence where the boundary between justice and personal vengeance becomes blurred. Meanwhile, the ghoul community itself is far from unified, encompassing factions that range from peaceful coexistence to extreme militancy.

A major turning point in the narrative lies in Kaneki’s psychological transformation. Severe physical and mental trauma – particularly experiences of brutal torture – completely dismantle his former weak self-image. Kaneki gradually abandons the desire to return to a “normal human” life, choosing instead a path defined by strength and survival, and ultimately accepting his hybrid nature. This transformation reshapes not only his own fate, but also the relationships and power dynamics within the ghoul world.

In later arcs, the story expands in scope, delving into political conspiracies, the historical origins of ghouls, and the true role of the CCG in maintaining social order. Characters who once played secondary roles are explored in greater depth, revealing individual motivations, beliefs, and personal tragedies. Tokyo Ghoul thus evolves from a personal narrative into a comprehensive portrait of a society sustained by fear, violence, and exclusion.

Through its multilayered narrative structure, Tokyo Ghoul guides readers from individual tragedy toward systemic critique, where the question “who is the monster?” no longer has a simple answer. This expansion provides the enduring appeal of the plot and lays the groundwork for deeper thematic analysis.

3. Themes and Ideological Concerns

Crisis of Identity and the Question of Being

The central ideological axis of Tokyo Ghoul is the crisis of personal identity within a society governed by classification and exclusion. As a half-ghoul, Kaneki Ken belongs fully to neither community, embodying a liminal state in which the self lacks stable grounding. The work does not treat identity as a fixed essence, but as the outcome of continuous friction between the individual and their environment, between subjective choice and external pressure.

Through Kaneki’s transformation, Tokyo Ghoul raises a fundamental question: what defines a human being – biological origin, moral behavior, or self-awareness? Kaneki’s forced consumption of human flesh is not merely a physical shock, but the collapse of the value system he once believed in. Identity, in this context, ceases to be a choice and becomes a burden imposed by circumstance.

Violence, Survival, and the Legitimation of Evil

Tokyo Ghoul approaches violence not as spectacle, but as a social mechanism. Within the world of the story, violence is legitimized through official discourse: the CCG exterminates ghouls in the name of justice and security, while ghouls justify cannibalism as a condition of survival. This symmetry destabilizes absolute notions of good and evil, replacing them with moral conflicts devoid of simple solutions.

The narrative demonstrates that when survival becomes the highest priority, ethical standards inevitably erode. Violence transforms from isolated acts into a systemic phenomenon, sustained and reproduced by collective fear. In this context, Tokyo Ghoul exposes a paradox: the more society claims to protect order and safety, the more it risks descending into dehumanization.

Discrimination, Exclusion, and Power Structures

Another significant theme in Tokyo Ghoul is the social construction of the “other” as a means of preserving superficial stability. Ghouls are labeled as monsters and stripped of legitimate existence, thereby enabling institutionalized violence. Yet the work does not limit its critique to human society; it also reveals similar hierarchies and power structures within ghoul communities themselves.

Through the CCG and various ghoul organizations, Tokyo Ghoul illustrates how power operates through discourse: those who possess the authority to name also possess the authority to decide who deserves to live or die. Classifying individuals as “human,” “ghoul,” “dangerous,” or “harmless” is not a neutral administrative act, but the foundation for life-and-death decisions. The work thus presents a sociological insight: violence does not originate from isolated individuals, but from enduring, invisible systems of power.

Isolation, Suffering, and the Desire for Recognition

Beyond social conflict, Tokyo Ghoul emphasizes profound spiritual isolation. Most characters, whether human or ghoul, exist in states of separation, unable to find spaces where they can exist authentically. Kaneki, Touka, Amon, and Arima represent different forms of loneliness, yet share a common desire: to be recognized as valuable individuals rather than tools or threats.

The work suggests that suffering arises not only from physical violence, but from the denial of identity. When individuals are not acknowledged for who they truly are, they must choose between erasure and resistance. This choice drives many characters toward extremity, deepening the tragic nature of the Tokyo Ghoul world.

Existentialism and the Tragedy of Choice

At a deeper level, Tokyo Ghoul is imbued with existentialist thought, repeatedly placing characters in situations where every available choice is flawed. Kaneki possesses freedom of choice, yet each decision entails loss, transforming freedom into a burden rather than a privilege. His tragedy lies not in the absence of choice, but in the inevitability of suffering regardless of the path taken.

Through this lens, the work depicts a world in which meaning is not given, but must be forged through pain and contradiction. Tokyo Ghoul offers no clear message of salvation, instead leaving readers with open-ended questions that demand personal confrontation with ethical and existential dilemmas.

4. Value and Influence

Artistic Value and Modes of Expression

One of Tokyo Ghoul’s most notable contributions lies in its redefinition of the visual language of psychological horror manga. Sui Ishida’s art style prioritizes atmosphere and emotional expression over polished aesthetics. Heavy use of shadows, rough linework, and stark contrasts generates a persistent sense of instability, directly mirroring the psychological states of the characters and their world.

Panel composition often adopts cinematic techniques, favoring close-ups of faces, eyes, and bodily details to emphasize internal conflict rather than surface-level action. The kagune – ghouls’ biological weapons – are designed with remarkable variety, functioning not only as combat tools but also as visual symbols of each character’s nature, emotions, and psychological damage. This integration of imagery and psychology creates a distinct aesthetic depth unique to Tokyo Ghoul.

Ideological Value and Social Critique

Beyond entertainment, Tokyo Ghoul possesses significant ideological value through its pointed social critique. Rather than merely depicting conflict between humans and monsters, the series employs ghouls as metaphors for marginalized groups. In doing so, it interrogates how modern societies construct norms, define “others,” and legitimize violence in the name of order.

Institutions of power within the narrative – most notably the CCG – are portrayed as systems driven by fear and control, reflecting real-world mechanisms of authority. By refusing to moralize any faction absolutely, Tokyo Ghoul avoids simplistic ethical narratives and instead invites readers into nuanced moral reflection.

Influence on Contemporary Japanese Manga

The success of Tokyo Ghoul marked a significant shift in manga creation for adolescent and adult audiences. The series demonstrated that manga could address existential, philosophical, and social themes while maintaining strong commercial appeal. In its wake, numerous works featuring darker tones, anti-heroic protagonists, and psychological crisis gained broader acceptance.

Furthermore, the portrayal of a deeply flawed, emotionally vulnerable, and constantly evolving protagonist like Kaneki Ken helped reshape character construction in manga. Protagonists were no longer idealized symbols of triumph, but embodiments of contradiction, failure, and painful choice – an influence that continues to shape subsequent generations of creators.

Cultural Impact and Reader Communities

At the level of popular culture, Tokyo Ghoul left a powerful mark through its anime adaptations, novels, video games, and related merchandise. Kaneki’s white hair and ghoul mask became iconic images, widely reproduced in cosplay, fan art, and online platforms, illustrating the series’ reach beyond manga readership.

More importantly, Tokyo Ghoul fostered a readership that engages with manga as an intellectual and reflective experience rather than mere entertainment. Ongoing discussions surrounding identity, violence, power, and existence demonstrate the depth of reception the work has achieved. This capacity to provoke sustained reflection is a key factor in Tokyo Ghoul’s enduring relevance even after the conclusion of its main storyline.

5. Conclusion

Tokyo Ghoul is not simply a dark-themed horror or action manga, but a work that profoundly reflects existential crises and moral conflicts inherent in modern society. By placing humans and ghouls within the same space of existence, the series compels readers to confront fundamental questions about humanity, the right to live, and how societies assign value to individuals. The deliberate ambiguity between good and evil constitutes the distinctive ideological weight of Tokyo Ghoul.

Kaneki Ken’s journey – from an ordinary student to a deeply scarred hybrid being – serves not only as a personal narrative but as a metaphor for individuals marginalized by social norms. His choices, whether driven by survival or resistance, reveal the harsh cost of freedom within a world governed by fear and violence. Through this, Tokyo Ghoul asserts that the greatest tragedy lies not in becoming a “monster,” but in being denied the right to exist as a meaningful human being.

With its expressive artistic style, multilayered narrative structure, and profound social critique, Tokyo Ghoul has secured its place as one of the defining works of contemporary Japanese manga. Its influence extends beyond entertainment and popular culture, opening spaces for serious dialogue about existence, power, and ethics in modern life.Ultimately, Tokyo Ghoul leaves readers not with a clear message of redemption, but with a series of open-ended questions that linger long after the final page. It is precisely this ability to provoke thought and challenge assumed values that allows Tokyo Ghoul to transcend the boundaries of conventional manga and stand as a significant milestone in the maturation of Japanese comics.